Bitter botanicals have been added to alcohol since ancient humans discovered alcohol in the first place, whether for alleviating ailments and afflictions or simple enjoyment of the flavors.

Use of gentian root, the backbone of many modern aperitifs, can be traced back over three thousand years to ancient Egypt, where it was used to treat a variety of stomach problems. Wormwood, another herb known for its incorporation in absinthe and other bitter spirits, first found use millennia ago as a bittering agent for early beer.

Herbs in Antiquity

In Sacred and Herbal Healing Beers: The Secrets of Ancient Fermentation, Stephen Harrod Buhner suggests that these plants were initially used by early brewers as their antimicrobial nature protected beer and its drinkers. According to Buhner, while early brewers were unfamiliar with the underlying science, they understood the process as being dependent on plants that possessed “sacredness and a soul.” Many early societies shared a belief in the significance of botanicals used in these bitter brews, and from this beginning emerged more general spiritual traditions. As cities were established in Egypt, Greece, and Rome, cults around gods associated with rebirth, agriculture, and beverages all evolved from these early beliefs on the use of bitter herbs.

The early centuries of Christianity were defined by competition with other theologies in the Near East, and Christianity ultimately incorporated elements of older religions. Dionysus, a Greco-Roman god, as well as his Egyptian equivalent Osiris, were connected to resurrection and the healing aspects of wine. Scholars such as Buhner have argued that the resurrection motif originally emerged as symbolism for fermentation of beer and the germination of seeds. The effect that these myths had on Christianity can be seen in some elements of Easter tradition like the crucifixion and the resurrection. Similarly, Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki became associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries, a Greek initiation ceremony that likely originated from an ancient agrarian cult. This ceremony was known for the use of a mysterious psychedelic beer called kykeon that simulated a descent into the underworld.

As Christianity grew, missionaries incorporated these existing cultural rituals in order to encourage converts. At the same time, rituals of Christian monasticism were established in Egypt and Syria. By the fifth century, Benedict of Nursia put forward the Rule of Saint Benedict, precepts that formally established brewing as a practice of Christian Monastic orders.

Among the best-known beverages in this tradition are the Trappist beers of Belgium, still brewed under direct supervision of monks. In Italy and southern France, many liqueurs, including Chartreuse and Averna, can either be traced directly to an order of monks, or incorporate this idea into their brand story. Over time, distillation of spirits and the concept of the apothecary came to Europe from the Arab world; many towns in the former Papal States still have monasteries which once featured an adjacent apothecary producing liqueurs. When combined with the knowledge of herbs and brewing from the monasteries, “bitters” as a distinct category was born along with the modern pharmacy.

Cocktail historian David Wondrich describes Richard Stoughton, a London pharmacist, creating a stomach elixir by mixing bitters with fortified wine from the Canary Islands as early as the 1690s. From here, the popularity of bitters grew into a Bitters Boom in the United States of the 1800s. Pharmacies touted the health benefits of carbonated water flavored with bitters and cordials, while their rivals, the saloons, used bitters to mask the harsh flavor of early American whiskey. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 ended the centuries-long relationship between bitters and pharmacies. Imbibers did not care that bitters were not quite the cure-all that they were originally promised to be, and continued their use in cocktails. Bitters became a staple of the bar, where they remain.

The Orinoco

In this long history, no brand of bitters would come close to having the cultural impact and longevity of the one developed by a German doctor in South America in the year 1824.

When Johann Siegert developed Doctor Siegert’s Amargo Aromatico, which almost two centuries later we still know as Angostura Aromatic Bitters, perhaps his timing was right to take advantage of that future Bitters Boom. Or perhaps he was just in the right place: the staggering botanical cornucopia of the delta of the Orinoco River.

Many tributaries, traversing diverse regions, flow into the Orinoco. Some of them originate in the Llanos, vast grasslands that span much of central Venezuela and Colombia. These grasslands support a wide range of plants in the genus dipteryx including the tonka bean tree or Brazilian teak. The seed of this tree has almost mythical status among American chefs due to its complex aromas of cherry bark, amaretto, and vanilla—and because consumption is prohibited by the United States Food and Drug Administration due to liver toxicity.

Also thriving on these plains is a group of trees referred to as bois bande. Believed to have aphrodisiac qualities, their bark is used in homemade spiced rum liqueurs all across the Caribbean, notably the Mama Juana of the Dominican Republic and the bush rum of Dominica.

Other streams that lead into the Orinoco start in the Guiana Highlands to the south. Angel Falls, the tallest waterfall in the world, can be found among them. This stream of water cascades down steep mountains called Tepuis before travelling through a network of tributaries. The flat tops of these tall plateaus are cool, moist, and often covered in clouds. Several exotic flower species with unusual medicinal properties evolved there in isolation from the rest of South America.

The most easterly of the Orinoco’s sources originate on the slopes of Colombia’s Cordillera Oriental. Early inhabitants of this area once made bittersweet concoctions with yerba mate, guarana, and coca leaves. They also consumed an alcoholic beverage made by fermenting forastero cocoa, a varietal known for being less aromatic but more bitter than the criollo cocoa from Mesoamerica.

The flora of the Orinoco basin found its way to the expansive Delta Amacuro area, either floating on the surface of the water as it flowed towards the Atlantic, or in the dugout canoes piloted by people like the Ye’kuana and Warao who, understanding the benefits of certain plants, brought them as supplies on their travels.

Records of the earliest Europeans in the region indicate that their survival often depended on the sharing of native knowledge. British explorer Sir Walter Raleigh recounted that the Amerindians saw him as an ally against the Spanish and used shrubs to treat his crew for fever. Ethnobotanist Cheryl Lans has suggested that this indigenous knowledge was combined with Spanish folk medicine that arrived in the region with the conquistadors. In her 2017 paper in GeoJournal, “A review of the plant-based traditions of the Cocoa Panyols of Trinidad,” Lans asserts that “Amerindian ethnomedicine lies at the center of ethnobotany” in the area that she refers to as the “Orinoco Interaction Sphere,” and existed in several tisanes and tinctures used to treat common ailments.

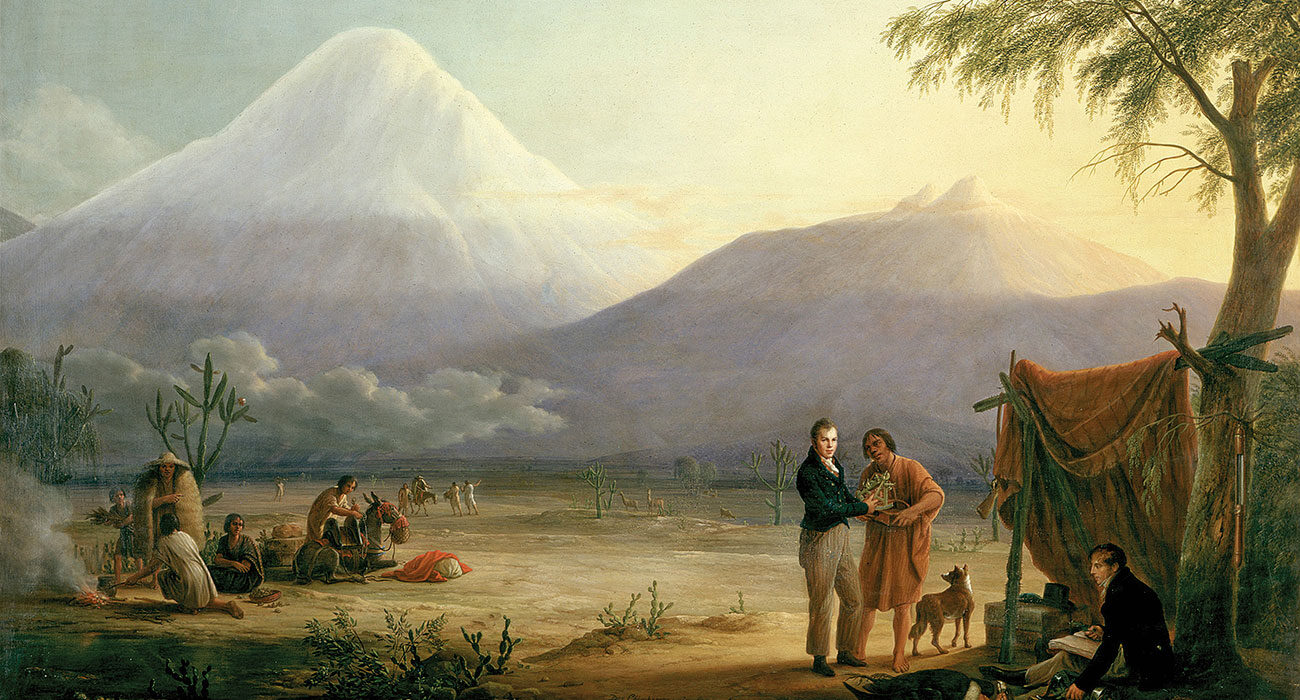

Humboldt

Although ethnobotany at the time was primarily an oral tradition, naturalist Alexander von Humboldt documented some of these practices during his exploration of the Llanos and the Orinoco at the end of the eighteenth century. In The Invention of Nature, historian Andrea Wulf’s account of how Humboldt came to view nature as a single interconnected system, she remarked that he marveled at the ability of his indigenous guides to “distinguish trees by the taste of their bark alone” and describe their myriad uses.

Gerard Helferich’s biography of Humboldt, Humboldt’s Cosmos, recalls several incidents of these cures being needed during his time in South America. On one occasion, a curandera (a healer in the folk medicine tradition) served the expedition party “a cold infusion of the bark of a shrub” that was described as tasting like licorice, in order to alleviate them of parasites. Helferich continues, “so effective was the cure that the travelers took some of the bark away with them, in case of reinfestation.” He also described Humboldt learning from a poison master how to make a paralyzing agent from vines, which could double as a palliative if administered properly.

Finally, in the town of Angostura, when Humboldt and two travel companions were stricken with typhoid, he was able to determine the most effective herbal treatments and send medical recommendations to Europe along with his extensive herbarium of previously undocumented plant life.

On his return to Europe, Humboldt was lauded as a celebrity. He had charted the most complete map of South America, written extensively on indigenous culture, and climbed what was believed to be the world’s highest mountain. Not only had he made invaluable contributions to botany, he also influenced Romantic literature and proposed paradigm-shifting perspectives on geography. In his home country, he was appointed chamberlain to the Prussian king, and he helped establish the University of Berlin, an institution that counted Johann Siegert among its earliest students.

Despite this, Humboldt considered Berlin dull and opted to remain in Paris, seeing the French capital as more suited to his academic work and the arduous task of publishing his journals. It was in this city that Humboldt would meet and form a friendship with Simón Bolívar.

Bolívar

Following the death of his wife, Bolívar spent some time adrift in Europe. The experiences of these years and the political discussions he had throughout them shaped his worldview and motivations for the liberation of his homeland, Venezuela. Biographers of both Bolívar and Humboldt agree that the former found inspiration in the latter’s appreciation for South America and his anti-imperial stance. The two men discussed the feasibility of a South American revolution when in Rome, but Humboldt had already left for Naples by the time that Bolívar made his famous vow to end Spanish rule of South America.

Letters written by Bolívar during his Admirable Campaign indicate a continued recognition for the man that he described as “the true discoverer of South America.” In France, Humboldt criticized Spanish rule in South America and encouraged both Europeans and North Americans to join Bolívar in battle.

Thousands of veterans of the Napoleonic Wars journeyed to Venezuela to fight for Bolívar. Among them was Johann Siegert, who would go on to serve as the Surgeon General in the government of the Republic of Colombia (encompassing modern Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, mainland Ecuador, and parts of Peru and Brazil) which was formed during the Congress of Angostura convened by Bolívar in that city from February 15, 1819.

Siegert

In Germany, Siegert had studied a field largely influenced by Humboldt at a school now named after him. In Colombia, he served under a military leader inspired by Humboldt in a town first made famous by him.

Due to the secrecy surrounding the formula for Angostura Bitters, and the fact that Humboldt burned many of his letters, it is difficult to ascertain the exact degree of influence that Humboldt and his work had directly on Siegert and his formula. But it’s easy enough to see that he was intrigued by one of Humboldt’s chief interests: the use of the Orinoco’s plant life to treat disease, and how this could be applied to medicinal tonics.

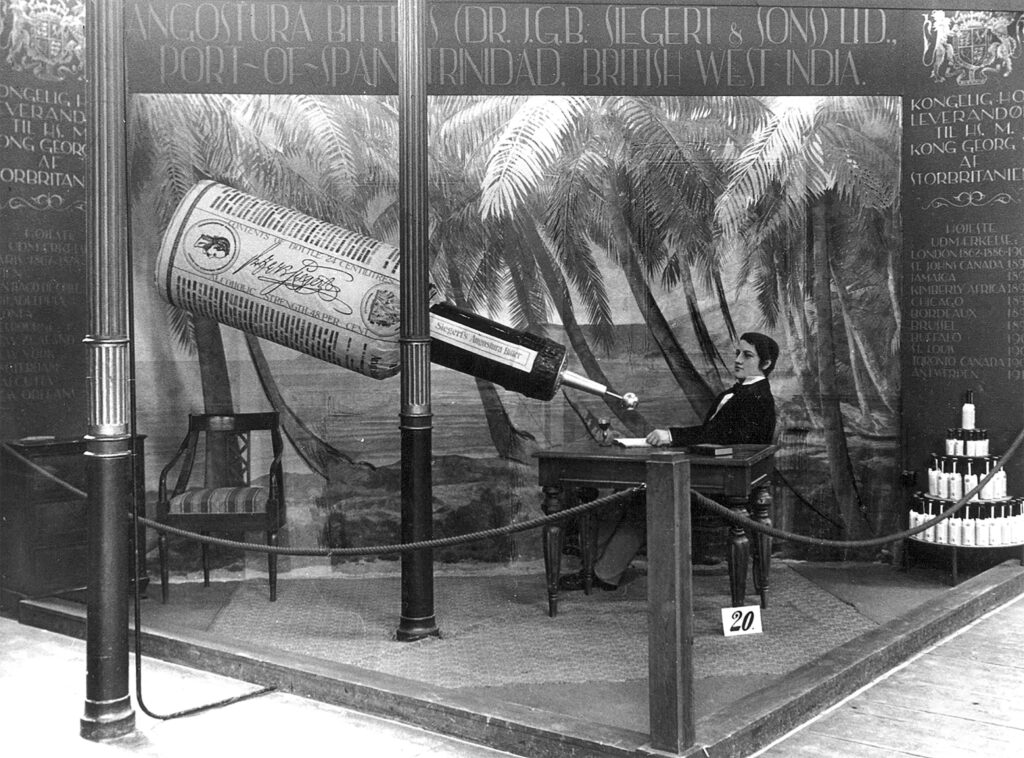

Remaining in the town of Angostura after the war, Siegert spent more time experimenting with these plants and learning from the tribes that had taught Humboldt. Within a few years of his arrival, Siegert had his bitter tonic formula. In later years, with the revolution complete, he moved production to a large island off the coast of Venezuela, where it remains today: Trinidad. For its pivotal role in that revolution, the town of Angostura became Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela. Yet the name lives on in the company descended from Siegert in Trinidad.

Gérard Besson, the curator of the Angostura Museum, once remarked that the botanical knowledge of Amerindians would necessarily have influenced the development of Angostura Aromatic Bitters. The House of Angostura’s chief mixologist, Raymond Edwards, shares this view, believing in its contributions toward “a product that worked well.” He concedes, however, that its origin in these folk medicine traditions was simply one of many factors in its success. Perhaps even more important was the ingenuity of Siegert’s promotion.

While traveling to introduce his brand of bitters to new markets, Siegert would always offer some to fellow passengers on ocean liners who might be seasick. Before even reaching the trade show or exhibition, he would have created lifelong customers on the voyage. As Edwards put it, Siegert was “a master marketer and highly respected doctor” who made personal connections with customers in the early history of the brand.

History Regained

How is it that the influence of the Orinoco and Humboldt to the development of bitters and cocktail culture remains so unknown?

The Orinoco has always played second fiddle to her sister river to the south, the Amazon. It has never been seen as being culturally significant like the Ganges or the Mississippi. Alexander von Humboldt, a man once considered almost as famous as Napoleon by his contemporaries, faded to obscurity as the sciences became specialized. With no single iconic discovery to be remembered for, he was eventually overshadowed by those whom he once inspired.

In spite of this, both have been honored by eponymous brands of bitters. Alex von Humboldt’s Stomach Bitters was produced by a Californian company in the mid-1800s. During this era, there was also an Orinoco Bitters being distributed by a company in New York. In recent years, the Orinoco Bitters name has been resurrected, and there is also now a brand of bitters named after Aimé Bonpland, the French explorer who accompanied Humboldt on his journeys.

Humboldt inspired Bolívar’s revolution, the decision of Charles Darwin to do field research in far-flung places, and even poets like Walt Whitman and Edgar Allan Poe. He was the first to propose human-induced climate change, and he developed a school of thought that saw scientific field work combined with the ideals of the age of Romanticism.

But, through Siegert and his peers, he invigorated an interest in the botanicals of the Orinoco region, which culminated in bitters as we know them today. Bitters, which are the ingredient that made cocktails possible in the first place, now drive a modern efflorescence in craft bars around the world.