A Discussion at Jungle Bird

The Planter’s Punch is a foundational drink, a gateway connecting the punch bowl of the seventeenth century with the tropical cocktails of the twentieth century. Many tropical drinks have a combination of rum, lime, and sweetener, but the Planter’s Punch is known for its addition of spice (often grated nutmeg or bitters) and is served long over ice. It’s associated with the nineteenth century in Jamaica where it developed as an individual serving of the ancient art of punch, which itself was brought to the Caribbean from its origin in India, where rum, citrus, and sugar, all originating in South Asia, were first combined.

Through tourism the Planter’s Punch spread around the world. It inspired the majority of the Don the Beachcomber oeuvre. But unlike other tropical drinks such as the Daiquiri or Mai Tai, it’s rarely ordered at bars today unless it’s on the menu.

On April 11, 2022, we met at Jungle Bird in Manhattan (the scene of our previous event back in the semi-mythical pre-pandemic era) with a dream team of four of New York’s top bartenders. Together they explored the opportunities of the iconic Planter’s Punch with six interpretations of the drink, showcasing their own creativity, a range of rum bottlings, and the possibilities of flavor combinations.

That dream team is:

Fanny Chu, Bacardí Premium Rum Aficionado and ex-head bartender of the much-missed Donna Cocktail Club.

Leanne Favre, beverage director for Clover Club and Leyenda.

Jelani Jah Johnson, distiller at the Great Jones Distillery and ex-head bartender of Gage & Tollner.

Garret Richard, Chief Cocktail Officer of the Sunken Harbor Club.

Ben Schaffer served as moderator.

The fierce bartenders keeping the Planter’s Punches pouring were Kiki Karatzas and Rachel Prucha. As always, thanks must go to Jungle Bird’s owner, Krissy Harris, and its events director, Marissa Cheshier.

We continue to be grateful to our stalwart sponsors: Appleton Estate, Bacardí, Denizen, Don Q, Mount Gay, Santa Teresa, Wray and Nephew, and Zelda Magazine. It’s been a pleasure bringing back our event series with you all.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity. — Ed.

Defining Our Terms

Ben: What does “Planter’s Punch” mean to you?

Fanny: The first time I had a Planter’s Punch was in Hawaiʻi. I was on a trip with my sisters, the first time we went there. I ordered a Planter’s Punch because I didn’t know any better. I was not a cocktailist or anything, I just liked to drink fruity drinks. It was made with passionfruit, orange, and guava and it was absolutely delicious. I honestly didn’t know what a Planter’s Punch was until I started working at Donna.

A guest came up and ordered it, and I was like, “I don’t know what it is, I’m going to look it up on my phone real quick.” A typical Planter’s Punch is one part sour, two parts sweet, three parts strong, four parts weak, although I think it’s changed so much nowadays with the different variations. But it’s supposed to taste like you’re taken away to the tropics. Lots of rum, lots of fruit juices, but everybody’s palate’s different.

Leanne: I grew up in Florida, and a lot of our tropical drinks are dependent on what bar you’re in. But for me, Planter’s Punch has always been something that was rum-based, full of fruit juices, and long. Something that’s a bit more on the refreshing side, to break that heat of mid-day. Beyond that, it depends on what juices they have in the bar. There’s no strong history in Florida of making drinks well, but I think they’re coming around a little bit.

Jelani: I think of the Planter’s Punch as more of a cocktail template than a recipe. That’s why you see it differently on so many different menus. Classically, though, if you think about the history of it, the sing-songy “one of sour, two of sweet” hearkens back to naval days. A kind of whimsical navy feeling translating to hotel and resort life.

The Planter’s Punch became the welcome cocktail at one of the first big hotels in Jamaica, the Myrtle Bank. All these American tourists would go down and drink it and be delighted by it. But it was marketed as just something simple. It’s Jamaican rum, which is such a flavorful component on its own. It opened everyone’s eyes to what spirits can be as opposed to just whiskey being whiskey, gin being gin. Rum, it’s different everywhere you go. It became this template for this new kind of cocktail, and everyone ran with it.

In a Planter’s Punch, you’re using rum, fruit juices, sugar, spice, and water. It really begins in the earliest days of punch as the classic five ingredients of sugar, citrus, spirit, water, and spice.

Garret: The Planter’s is really a twentieth century holdover from the nineteenth century. In the nineteenth century, there were American bartenders making single-serve punches in an extension of the punch era of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. You’ve probably seen these single-serve punches in cocktail books. You see the Curaçao Punch, which Dale DeGroff is a big proponent of. You see the Knickerbocker, which is sort of a fix, which is a kind of single-serving punch. All of these single-serving punches went by the wayside but the Planter’s Punch survived.

It happens to be a really good vehicle for the category of black rum, rums of the time like Wray and Nephew, Dagger, and Myers’s. Myers’s was a huge brand, which contributed a lot to building the Planter’s Punch into a category. As Jelani was saying, the success of this single-serving punch then forced bartenders on other Caribbean islands to riff on it. But I think without it, it’s hard to think of what Caribbean cocktails and Caribbean-inspired cocktails would look like. They wouldn’t look the way they do now.

Ben: What separates Planter’s Punch from other tropical drinks involving rum, citrus, and sugar?

Jelani: I don’t think that there is an answer to that because of the trajectory that tiki took. Don the Beachcomber, Trader Vic, Joe Scialom, everyone who pioneered tiki cocktails as we know them—they worked from templates. Let’s say the Zombie, where Don the Beachcomber took the template of the Planter’s Punch with certain measures of sugar, citrus, spice, and spirit. He’s like, “Why don’t I mix different spirits? Why don’t I mix different spices?” He basically did the kitchen sink approach to mixing all of these flavors together and created one of the most delicious and immortal tiki drinks that we’ve ever seen. I would argue that it was based on the Planter’s Punch.

Garret: There’s a cocktail that’s going through this right now. It’s called the Negroni. It’s getting to the point where bartenders wonder, “What the hell actually is in a Negroni?” Because there’s so many different types. We have a drink at Sunken Harbor that has mezcal, banana cordial, Cap Corse Blanc, and Suze, and we say it’s a Negroni equivalent. But it’s far from the original. Like Jelani said, you have to look at it as a template. Planter’s Punch is spice, rum, citrus, and sweetener and obviously the weak, which is also an area to experiment with. You could probably do Planter’s Punch with kombucha if you wanted to.

Leanne: Yeah, I think the weak part of the Planter’s Punch is a defining aspect. When I think about what a Planter’s Punch is, it’s supposed to be long and refreshing.

Planter’s Potion by Garret Richard

5 drops 20% salt solution

3 dashes Angostura bitters

1½ oz Jasper’s Mix (see Jeff Berry’s Potions of the Caribbean, p. 265)

1½ oz cold-brewed Assam tea

¾ oz Wray & Nephew Overproof Rum

1½ oz Appleton Estate 8 Year Reserve Rum

Flash blend with 8 oz of pebble ice for 5 seconds. Pour over 4 oz of pebble ice in a Hurricane glass. Garnish with grated nutmeg and mint. Serve with a straw.

Jasper LeFranc’s Legacy

Ben: I wanted to start with this particular drink because I think it’s the most traditional of the six that we’re having today. We’re calling it the Planter’s Potion because it’s inspired by the centrality of the Planter’s Punch in Jeff Berry’s book, Potions of the Caribbean. Garret, tell us how this drink came together. And who is Jasper and what is his mix?

Garret: A big part of my cocktails, and what we do at Sunken Harbor Club, is to take pieces of different historic recipes and combine them. The Planter’s Punch is a great template for that. You’ll see in the recipe that this cocktail has tea in it, and that came from a New York Times article in 1957 about the Lemon Hart rum company, talking about why the Planter’s Punch is great, why you should drink it, while promoting their rums. At the time, Lemon Hart made Jamaican rums as well as Demerara rums from Guyana.

They interviewed someone named Colonel A.R. Woolley, which is a very scary name, and the colonel said that in order to make a Planter’s Punch the way it’s enjoyed it in the tropics you cut your punch with tea rather than water. The tea gives you flavor, it adds tannins to the rum, it gives you an extra layer of fruit.

Jasper LeFranc was one of the most famous bartenders during this time. He was an African Caribbean bartender working at the Bay Roc Hotel in Montego Bay in Jamaica, where he was a huge star. People went there specifically to have his cocktails.

Think about a high-volume resort, which is constantly making cocktails all day. Jasper LeFranc had an interesting solution. He thought, “What if I make one basic mix that can be combined with different rums, different liqueurs, and make multiple cocktails across the menu?” Essentially, what he made was a craft version of sour mix. Then he was able to create his own menu based on it. His rum punch was the mix with Wray and Nephew, his Planter’s Punch was the mix with either Coruba or an expression of Appleton that existed then called Appleton Punch, which was a darker, molasses-forward rum.

Jasper’s Mix is a well-balanced cordial that you can build all sorts of things on top of. The nice thing about this drink is the tea and the cordial work out to a perfect balance.

So why do we know about Jasper LeFranc? Shirley Sarvis was a writer in San Francisco, a huge advocate of San Francisco cuisines and San Francisco food and wine. She started working with Trader Vic, helping to write some of his later books in the ’60s and ’70s. She wrote an oddly-named one with him called Trader Vic’s Rum Cookery and Drinkery in 1974. She went down to the Caribbean for research, interviewed Jasper, and got recipes from him directly. Essentially, she was doing Jeff Berry work before Jeff Berry was Jeff Berry.

Some of Jasper’s work also came through famous rum collector Stephen Remsberg. Stephen is a huge fan of his work and eventually gave the mix recipe to Ted Haigh to put in his book Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails. So, all together, this drink is a tribute to an old-school style of Planter’s Punch.

One thing that became apparent when learning about Stephen Remsberg’s collection is that Jamaican rum from yesteryear was molasses-forward and funky. Now, I think we have those two qualities split into different products. I think it’s up to the bartender to blend them back together. We have a million different options, so I’m not complaining about why a certain bottle doesn’t exist anymore. It actually gives us more freedom and more ability to dial in our own expressions.

Fanny: Did you try to recreate rums like the Wray and Nephew 17?

Garret: What comes to mind more than anything when I’m working on any sort of rum punch is a defunct brand called Lowndes. The first time I got to meet Remsberg, he talked to us about Lowndes, which was a Jamaican rum used in the Zombie. He said, “I worked my butt off to try and recreate it. The simplest way I’ve found is cutting Coruba with a pot still Jamaican, fifty-fifty.” That taught me a lot about how to blend rums and how to make them work for cocktails.

Cordials

Ben: Garret, you said that you think of Jasper’s Mix as a cordial?

Garret: Yeah. The way the recipe for Jasper’s Mix was given to Stephen Remsberg is very, very loose. It’s “take some lime juice, add sugar until you think it’s sweet enough, finish with Angostura bitters and nutmeg.” Jasper was probably doing it largely to taste, and taste is subjective, right? What does it actually mean as a recipe?

When I started working at Existing Conditions, I learned how to adjust ingredients to measurable amounts of sweetness, rather than subjective taste. We measured sweetness in degrees Brix, which amounts to the percentage of sugar in a solution. I decided to take lime juice and bump it up to the sweetness of a cane or a Demerara syrup, which is 66 Brix, meaning two to one: two parts sugar, one part water. With the Mix as a known sweetness, I could slot it into things I already knew.

Jelani: I always love hearing you talk about how you come up with your cocktails based on numbers, using refractometers and Brix. We’ll taste my drink at the end, but I based my spice blend on Jasper’s Mix as well. But I used the “taste it until it tastes good” method, and that’s the only method that I have ever used. But now I’m thinking, “Why didn’t I think to find the Brix of cane sugar syrup and then make a consistent cordial based on it,” instead of trying ten different ways—lime with some zest in it, lime with no zest, juice of a big lime, juice of a small lime. I love comparing how we tackle the same things.

Garret: As long as we get to a point of deliciousness, that’s all that matters.

Fanny: Sometimes, it’s fun to go through all the little changes.

Jelani: Either way, you’re going to do all the R&D and have to try it a million times, but I really enjoy seeing the difference in methods. So what’s the best definition of a cordial?

Garret: In the context of a bar, if you’re making a syrup, it’s just a mixture of a large amount of sugar with flavors. A cordial adds a little bit of liquor to preserve it. It’s different from a syrup because of the alcohol.

Leanne: I always think as a cordial as contributing a little bit more texture, a little bit more acid, like a mouthfeel. It’s got the zest, it’s got the flavor. And the fortification.

Fanny: Sustainability is key for me because it lasts longer than most syrup, because it’s fortified. If you zest some citrus, you can add sugar to the waste, make a cordial out of that. It’s reusing, repurposing.

Garret: The problem with preserving citrus in a cordial is eventually the citrus starts to die out. You have something that’s cool, but it doesn’t have that bite anymore. So for the Jasper stock, I do one more step and finish it with the acids, citric and malic, that are already in lime. The bite can then sit for an indefinite time. If you have really high volume, this is not a problem—they were probably going through it pretty fast at the Bay Roc Hotel, but in a regular cocktail bar, you have to think about what it’s going to taste like a week from now.

Ben: Leanne, do you use cordials in your menus at work?

Leanne: I work at a heavy Margarita bar. Despite this being a rum conversation, when you’re working with lime and sugar and tequila or rum or any base spirit, it makes such a huge difference to find a way to be consistent no matter the season, no matter the size of the limes, no matter how much sweetness they’re offering. Whether that’s with acid adjusting or making a cordial, it’s about dialing in an ingredient that you can make in a large batch. It’s an important concept that I use all the time at Leyenda.

Fanny: I use Jelani’s method just because I’m a scientist. What I learned is the more you fuck up, the more you learn. Steve Jobs did that with Apple, and that’s kind of my method.

Ben: Well, he set a good example.

Leanne: Also, there’s a concept in cocktail making where you find something that tastes good and then you see how far you can push it until it doesn’t taste good anymore. Then you go one iteration backwards, which was the ideal solution, and that’s where we should land.

Jelani: You always have to cross the line to find it.

Leanne: Yeah, exactly.

Fanny: I’m all about crossing the line.

Salt

Ben: Several of our drinks tonight feature salt. What’s the role of salt in the progression of cocktails?

Leanne: When I approach cocktails, I’m always thinking about the culinary aspect and how flavors work with each other. Salt always helps brighten, highlight, bring out nuances. It can also balance a little of that sweetness if you find that it’s tearing one way or the other. Every cocktail with saline is going to be more expressive and pop.

Garret: I think you’re going to see salt as a standard part of cocktail recipes in probably five to ten years. A lot of that comes from the work of Dave Arnold. When I first started working with him, I noticed that salt connected the sweet and sour elements really well. I believe salt blocks some of the bitterness of fresh citrus and enhances the sweet elements that would be found in a syrup or liqueur.

That means you don’t necessarily have to drown your cocktail in—let’s call it that lemonade mix. I think everybody’s had that kind of craft cocktail bar Daiquiri with a lot of lime juice and a little bit of sugar. That can be fine if that’s what you’re looking for, but sometimes it’s really overwhelming to your palate. Having the salt element allows you to bring all those elements down so you can taste the different layers. It makes for more sessionable cocktails.

Jelani: I agree with Leanne and Garret, but in a lot of modern cocktails the use of salt is a little willy-nilly. I think that classics should stay classics, and adding salt doesn’t necessarily make them better. More people will learn how to use salt, but I don’t think it will become a standardized thing you’re going to see everywhere. I’ve used salt sparingly and only in a flavor wheel way of thinking. I think of salt as a direct counteraction to bitterness and as an enhancer of sweetness.

If something is not sweet enough, instead of adding an extra quarter ounce of citrus, I’ll add a pinch of salt that’ll play off the sweetness that’s already there. What I love to do in tiki cocktails is hyper-exaggerate the bitterness, adding a teaspoon of Angostura bitters and a pinch of salt. Next time you’re having a glass of amaro, play with it a little, put in pinch of salt to bring out the sweetness and cut through that rootsy bitterness. Salt can tone down a heavy hand on the bitters.

Lani Kai by Leanne Favre

2 dashes Angostura bitters

1 tsp allspice dram

½ oz rich Demerara syrup

½ oz orange juice

¾ oz lime juice

2 oz Don Q Reserva 7 Rum

Shake with ice cubes. Strain over pebble ice into a highball glass. Garnish with grated nutmeg and an orange wheel. Serve with a straw.

Contemporary but Traditional

Ben: Leanne had the task of coming up with two distinct versions of the Planter’s Punch. Tell us about your process for taking it in two directions.

Leanne: I looked through the history books at some of the older templates. I was inspired by what bars were doing what, when. I looked at the Planter’s Punch that they featured on the menu of Lani Kai, Julie Reiner’s tropical bar that was in the city a few years back. I adjusted that drink to my specifications.

Like Jelani said, I wanted to focus on citrus juice and spice. That’s staying classic, using allspice, nutmeg on the nose, and then a blend of juices. I saw many examples of Planter’s Punch throughout history that used orange juice. I wanted to feature that, knowing that it’s a challenging cocktail ingredient. It tends to make cocktails flat and is begging for acid. But I didn’t want to add acid here. I wanted it to be easy and refreshing. The Don Q Reserva 7 is a lighter, more delicate profile, really approachable with its own tropical fruit notes that go with the juices in the classic approach to this cocktail. I added lime juice to balance it out and keep it simple. It’s crushable, refreshing, and on the traditional side.

Island Kiss by Fanny Chu

3 dashes The Bitter Truth Peach Bitters

3 dashes El Guapo Polynesian Kiss Bitters

¼ oz simple syrup

¼ oz lemon juice

2 oz Hawaiian Sun Pass-O-Guava Nectar

1½ oz Bacardí Reserva Ocho

Briefly shake with 3 ice cubes, pour unstrained into glass, and top with pebble ice. Garnish with mint and an orange slice.

Hawaiian Punches

Ben: Fanny, your punch has a Hawaiian feeling, talk us through that.

Fanny: Yeah, it’s from the POG experience. My sisters do not drink—

Ben: A real hush went over the room there.

Fanny: It’s frowned upon. But POG [Passionfruit, orange, and guava, a popular Hawaiian blend. —Ed.] juice is what they love drinking, and this drink is an homage to my sisters and to our travels together. A lot of my drink creations are based on my experiences with food and drink and travel. So the Island Kiss is a little kiss to that.

Bacardí uses blackstrap molasses. I like utilizing that with my peach bitters because the rum has peach, apricot, stone fruit notes. The El Guapo bitters has all the tropical fruits in it. The guava, the coconut, the pineapple, which go along with the POG juice. I feel like the Bacardí Ocho is a flexible and delicious rum to play with any kind of tropical cocktail.

Garret: We’re talking about Hawaiʻi and we’re all in relatively the same age category. Hawaiian Punch—does that ever come to mind when thinking about the Planter’s Punch?

Fanny: Always.

Jelani: Actually, I always think of Hawaiian Punch, but not in terms of Planter’s Punch. Every time I’m trying to make a Singapore Sling, the flavor that I’m trying to avoid is Hawaiian Punch. But you want it to be Hawaiian Punch-esque because even though it’s Bénédictine, Cointreau, grenadine—

Ben: Classic Hawaiian Punch flavors.

Jelani: Yeah, but that makes you wonder what is Hawaiian Punch? But for me, the Singapore Sling, even with the most top-shelf ingredients, the most beautiful ingredients, it always tastes like Hawaiian Punch out of a juice box.

First Audience Member: Since we’re talking about Hawaiian Punch, what do you guys think about fassionola? Because it is a blend of fruit juices, red like Hawaiian Punch.

Ben: Fassionola, for those who don’t know, is a kind of mythical tiki syrup that different people interpret in different ways. There is also more than one flavor of it; there’s a red, a gold, and a green. The red one, Garret, do you want to talk about that?

Garret: When you read recent books on tropical drinks you see passionfruit syrup. But midcentury, there was a company called Jonathan English that decided to start making passionfruit syrup, but cut with other flavors, which it called fassionola. The idea, I’m sure, was more economical than anything else. Passionfruit’s expensive, even today, let alone in the 1950s. But we can cut it with other fruits and then make a syrup out of it. The one that everyone knows about is the red, which purportedly was in the original Hurricane at Pat O’Brien’s.

Connecting Flavor and Culture

Ben: Here’s something I’m wondering about. Basically, tropical drinks are of Caribbean origin. But some of these flavorings are what we think of as Hawaiian or Polynesian. What’s that link? Is it a flavor link because they are all based on tropical produce?

Fanny: Maybe, but maybe it could also be Elvis Presley’s fault for bringing us the Blue Hawaii. He brought out how amazing it is to go to Hawaiʻi, so maybe he is to blame for Hawaiʻi being more in tune with rum and tropical drinks rather than the Caribbean.

Garret: The reason, I think, for this sort of connection is Harry Yee. He was a Hawaiian bartender, very well aware of the work of Donn and Vic. But he decided to interpret drinks in his own style. He understood that people wanted these elaborate rum punches. Then he said, “I’m going to make them Hawaiian.” He gave it an identity. He’s the one that created the umbrella in the drink. He’s the one that put in the orchid in the drink. The reason we can do that now is because of Harry Yee.

Fanny: To piggyback on that, a lot of tropical drinks were also in Chinese restaurants. I remember when I was about three years old and my dad was working as a chef over in California at a Chinese restaurant. The first time I walked into the bar there were these Maraschino cherries and they had all these tiki mugs. I was always fascinated by it.

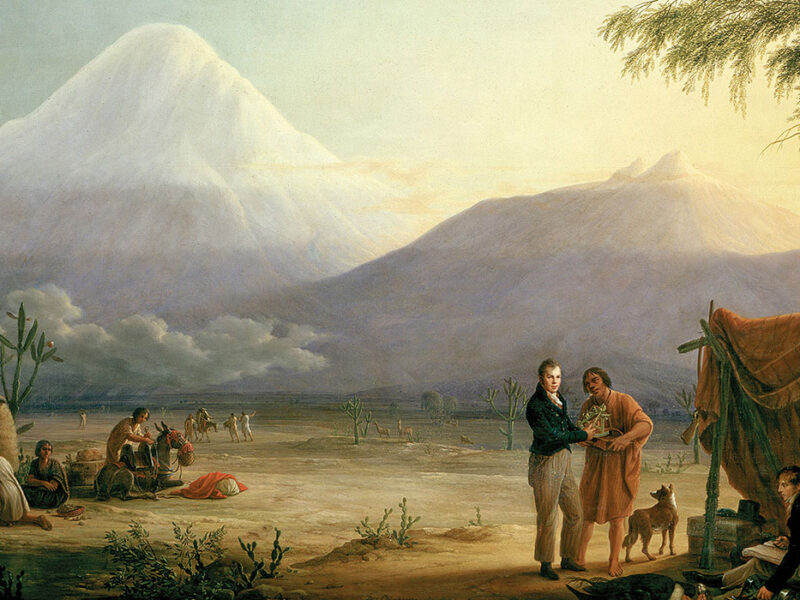

Jelani: I’m thinking about where to draw the line without turning this into an entire discussion on the merits of tiki. Tiki is the brainchild of a small handful of white men. Don the Beachcomber went on this puddle-jumping, world-traveling adventure. He saw so many cultures and cherry-picked aesthetics that he liked, creating the first tiki cocktails as we know them today. I think that’s why so many of the lines are blurred. It’s a Caribbean drink, but it’s served in a Chinese restaurant with these Polynesian idols and nautical themes. Then it’s all Americanized to be easily digested by the Hollywood, and later, suburban consumer—how does that all mesh?

In brutal terms, it’s cultural appropriation, where he took pieces that we like from less-privileged countries around the world and whitewashed them and Americanized them for his own profit. He made a ton of money and created something that we can enjoy today, even though it bastardized and Disneyfied a lot of world cultures. But it’s important to look at tiki from a bird’s eye view and understand that no, it’s not Hawaiian, it’s not Caribbean, it’s not Polynesian, it’s not Chinese. It’s a mixture of all these things that were handpicked by Americans in the ’30s through ’50s to create a very specific subset of imagery that they would want to see.

But the flavors are all Caribbean. Tiki is Caribbean cocktails served on a platter of facets of purposefully misrepresented global cultures for profit.

Ben: But that’s what being American is, right?

Jelani: Exactly. Love it or leave it, right? But really, that’s what it is. I’ve been hearing a lot that the fact that these lines are blurred is extremely problematic today, and that we should cancel tiki. But I think it’s more important to grapple with that and really understand where it comes from. You can’t just say that tiki overall is inherently bad, because it’s a part of history and it’s part of our shared past too. We have to see it for what it is, and yes, really own the fact that a lot of it was racist and problematic, in order to enjoy it holistically going forward.

Second Audience Member: To piggyback on Jelani’s sentiment, with tiki, tropical drinks, we’re searching for a narrative for the twenty-first century, based on contemporary enlightenment, for lack of a better word. But what struck me as each of you were talking about what Planter’s Punch is and what it evokes—there’s an opportunity to think and talk about the Caribbean sugar planters and what they did. That can carry a lot of meaning about the whole rum trade. But it is an opportunity to address that narrative—in a cocktail.

Jelani: Absolutely. It’s important, in my opinion, to acknowledge and reconcile all of this dark history that we come from. The right thing to do is to acknowledge and internalize the fact that a lot of these really fun things that we have enjoyed come from very problematic and very dark times. And for us to look back at them, and still enjoy Planter’s Punch, but to also talk about the history of it. I know this wasn’t supposed to be a discussion of our dark history as a country, but it is so important to address.

Ben: For a long time I didn’t want to name this event after Planter’s Punch because, just to clarify, “planters” refers to the sugar plantation owners, who were, of course, slaveholders. It’s the drink that they would have. I thought, should we try to retire the name? Maybe we should. But before this event, I wasn’t sure what that name could be. It’s a rum punch that’s specific, it’s not just rum punch. But I’m cool with giving it a new name if we can come up with it.

Third Audience Member: Emancipation Punch.

Jelani: If you had changed the name, we wouldn’t be able to have this conversation about our dark past as a nation.

Fanny: That may be the reason why you aren’t seeing Planter’s Punch on menus.

[Well, we didn’t solve it that night, but your comments are welcome. — Ed.]

Zombie Village by Leanne Favre

5 drops 20% salt solution

¼ oz cane syrup

¾ oz pineapple juice

¾ oz lemon juice

¾ oz white creme de cacao

1½ oz Mount Gay Black Barrel Rum

Shake with ice ice. Strain over ice cubes into a rocks glass. Top with 1 oz sparkling wine. Garnish with pineapple fronds.

Sparkling

Leanne: For my second drink I definitely wanted to go a in completely different direction. I looked at Skipper Kent’s recipe from 1954. Instead of using lime, which felt standard, and orange juice, which was common, he was using lemon and pineapple. For me, personally, that fits my flavor profile a bit more. Mount Gay Black Barrel is a nice, round, wooded rum, with rich vanilla notes, all of which connects to the earthy tones of the cacao. It’s a good pairing with pineapple and lemon.

As a bit of a modern touch, I threw a splash of sparkling wine on top of that to brighten it up. That effervescence helps with the aromatics, too. And with the pineapple and the sparkling wine, I get almost a tepache note. It’s a little more savory than you expect, which makes it the perfect platform for salt, as we were talking about.

Jelani: The Planter’s Punch gives you so much leeway to play with. If you just take it as a punch recipe, then the sky’s the limit. I’m blown away by the use of the sparkling wine in this drink, because if you think of the sparkling wine as the weak component, it makes a completely different cocktail.

Lost Navigator by Garret Richard

5 drops 20% salt solution

2 dashes cardamom tincture (see below)

3 dashes Angostura bitters

1 tsp vanilla-sandalwood syrup (see below)

½ oz lime juice

½ oz orange juice

3/8 oz cinnamon syrup

1½ oz Santa Teresa 1796 Rum

Flash blend with 4 oz pebble ice for 5 seconds. Pour over 2 oz pebble ice and 2–3 cracked ice cubes into a rocks glass. Garnish with a channeled lime twist and an orchid dusted with five spice powder. Serve with a straw.

Cardamom Tincture

7.5 g whole green cardamom pods

250 mL 151 proof neutral spirit (such as Devil Spring Vodka or Diamond 151 Rum)

Crack the cardamom pods into small pieces with a few pulses of a spice grinder. Toast the cracked pods in a saucepan over medium heat until aromatic. Let the pods cool and place them in a container. Add neutral spirit to the container and let it steep for 48 hours. Fine strain and bottle. Yields 250 mL.

Vanilla-Sandalwood Syrup

1 vanilla pod

1.25 g food-grade red sandalwood powder

227 g white sugar

227 g water

Cut the vanilla bean in half lengthwise. Scrape the vanilla beans into a saucepan. Cut the vanilla stalk into small pieces. Add the cut vanilla stalk, sandalwood powder, sugar, and water to the saucepan. Bring to a boil. Cover and drop to low heat for 15 minutes. Remove from heat, keep covered, and let sit unstrained for 12 hours. Strain through a fine mesh filter, bottle and refrigerate. Will keep for 2 weeks in the refrigerator. Yields 16 oz.

Aromas

Garret: Dusting the orchid with five spice powder is a move that I took from Audrey Saunders, who at Pegu Club was interested in offering aromatics on napkins or coasters or flowers, dusting with grated spices, or a tincture, something that gets your nose involved.

That leads me to the inspiration of the drink. One of Donn Beach’s famous riffs on the Planter’s Punch is the Nui Nui, another spiced rum punch. In the Caribbean, there are many different versions of spiced rum, like mauby. Instead of making a million infusions, Donn decided to take something like mauby and break it into smaller ingredients. These flavored syrups became Don’s Spices, each with a focus on different spices and juices. When Jeff Berry came to research Donn’s recipes, he had to determine what was in those spice mixes that the recipes used, and what he determined led to our understanding of what the drinks should taste like.

The jumping off point for this drink was changing the spices in the Nui Nui. The Nui Nui is focused on cinnamon, vanilla, and allspice. I 86’d the allspice, because I’ve used it a lot. I decided to get out of my comfort zone. I added cardamom. Cardamom punches up orange juice, as Leanne was talking about earlier, it prevents orange juice from being flabby. Then the five spice powder on top. Then sandalwood, which enhances the character of vanilla.

Santa Teresa 1796 is a really great base for that. This is the genius of the original Nui Nui, where Donn said, “Let’s take a good rum base and add spices to it,” rather than use a spiced rum that’s neutral and not amazing. Santa Teresa 1796, with its cherry notes and all of the barrel aging that it has, can stand up to this intense spiciness.

Jelani: Again, in terms of the history of tiki, what I get from this is sarsaparilla. Sarsaparilla is an ingredient that Donn Beach just fucking loved, because the one piece of Americana that he added to tiki was the soda fountain culture. He would use a ton of vanilla, sarsaparilla, root beer flavors. If you look back at the original soda jerks of the time, they were really the original mixologists. They were creating syrups. Don’s Spices is vanilla syrup and allspice syrup. Donn Beach was just an incredible guy. He had great taste. He knew how to pick things from different places and put them together into one thing and just make it amazing and give it to you on a silver platter. But this drink in particular really reminds me of an Americana soda fountain flavor profile.

Dilution

Ben: The more I learn about cocktails, the more it seems that dilution is the crux of everything even though it doesn’t get stage time. In our six drinks we have different approaches to it. Both of Garret’s drinks are flash blended. Jelani’s actually has water added directly. He also uses a whip shake. But before all that, can we talk about the importance of dilution? Again, it’s the weak part of the punch concept, but obviously it’s in every cocktail.

Leanne: Absolutely, dilution is one of the most important aspects of cocktails. Without the water, you’re not getting the full spectrum of flavor, you’re not getting the balance, and things start to feel really tight. Whether it’s stirring, shaking, or adding the water directly, it’s crucial to the inevitable build of your drink.

Fanny: Ice to us is heat to chefs, right? This is how we make sure our cocktail is tasting properly. If you’re tasting a spirit neat, you add a little drop of water or even soda water, it opens up so much of what the spirit is supposed to taste like. Imagine what it’s like with a cocktail. You get crushed ice, Kold-Draft, big rocks. You put five cubes of Kold-Draft or a large rock with something like pebble ice to agitate it and you get a certain frothiness in your mouth. That’s what we’re trying to go for. A Daiquiri, if you don’t have that froth, is that even a Daiquiri? Is it properly diluted? Dilution is very important. Water is life!

Ben: Garret, you want to talk about the flash blending technique?

Garret: Remember the first time you went into a craft cocktail bar and got an Old Fashioned on a big rock and you were like, “Oh my god, I never want another Old Fashioned on small ice again.” To me, flash blending is the crushed ice equivalent of that. With flash blending, you’re measuring the amount of ice that you have in the glass, so you’re getting a consistent amount of dilution every time.

Jelani: Am I going last? I have a lot of unpopular opinions on this.

I was really intrigued by the idea of grog. You look at Donn Beach’s Navy Grog, that’s another maximalist approach to Planter’s Punch. But then, in essence, grog is just a Planter’s Punch pared way down. My grog recipe was how I learned about different rums. I would do two ounces of rum, three quarters of an ounce of lime juice, half an ounce of Demerara sugar syrup, and then two ounces of water. I would drink it at room temperature, usually with nutmeg. It was a really awesome way to just taste through rums and play with dilution while having rum punch. I went through this exercise trying to turn people on, “Taste this, it’s a room temperature cocktail. It’s delicious.” Half the people were into it, half the people weren’t.

Ben: Why did you feel it had to be room temperature?

Jelani: That was me nerding out about the origins of where tiki cocktails came from. How did they drink on the ships when they had their rum ration?

Ben: I see, although I guess that was actually ship temperature. Cabin temperature.

Jelani: It might come from a distiller’s perspective. The first part of my day, every day, I start the still and taste the heads, 160 proof, they burn your mouth, taste like shit, you spit them on the ground and do it until it tastes good. Then later in the day, you do the fun job of proofing it down. You take this high-proof booze and add water gradually so you don’t mess it up and overshoot because you can’t take the water back out. But as you add water to spirit, it does really miraculous things at every single gradient.

For me, in terms of cocktail creation, I like to find that sweet spot in water content, where I can taste it, and where I’m going to like it. It’s hard at a cocktail bar to train people in how you shake, how you stir because it’s different for every single drink. With the Planter’s Punch that I made, I cut out the middleman and just added the water straight to the drink. Because it’s three quarters of an ounce, it wants three quarters of an ounce of water in order to be that nice level of dilution where you get enough spice and spirit carrying through.

Jelani’s Punch by Jelani Jah Johnson

5 drops 20% salt solution

½ tsp spice-infused Angostura bitters (see below)

½ oz rich Demerara syrup

¾ oz water

¾ oz lime juice

¾ oz pineapple juice

2 oz Denizen Merchant’s Reserve Rum

Whip shake. Strain into a Collins glass over pebble ice. Garnish with pineapple fronds, a lime wheel, and an orange slice. Serve with a straw.

Spice-Infused Angostura Bitters

3 oz Angostura bitters

1 cinnamon stick

1 whole nutmeg

2 coffee beans

Grind whole spices in a spice grinder and let them steep in the bitters for 1 week.

Punch in a Bucket

Jelani: When we closed the Owney’s distillery, I was sent home with a milk crate full of still-proof booze. We filled up two tanker trucks with rum and shipped them off to Indiana to store. But what was left in the hoses from the transfer was enough to fill three milk crates full of bottles. I was like, all right, I’ve got a milk crate full of still-proof booze. What am I going to do with it? It’s fire hazard in my hallway. I might as well come up with a way to make a punch out of it.

For the first iteration of this Planter’s Punch, the medium was a Lowe’s bucket. The recipe was two bottles of still-proof booze, two quarts of water, three cups of lime, two cups of pineapple, two cups of sugar. Then three ounces of this spice blend that I made based on Jasper’s Mix. Nutmeg, in particular, plus cinnamon and lime. Instead of adding that straight to the drink, I took a few ounces of Angostura bitters and put crushed spices in those bitters, and created a super tincture. Then I added it to taste to this bucket of punch.

It was so intense, I was like, “Okay, I fucked this up. I wasted two bottles of still-proof alcohol. I still have to serve this to my stupid friends. What am I going to do?” That’s where I came up with the salt thing. It’s way too bitter, so look at the flavor wheel. How do you counteract bitterness—salt. That’s it.

Ben: This drink is whip shaken, which basically means a briefer shake because there’s already dilution built into it, right?

Jelani: There’s already water in there so you can throw “some,” I always say “some ice” in a shaker and shake it for a couple seconds.

Ben: So this started with still-proof rum in a Lowe’s bucket. Now today we’re doing it with the rather more refined Denizen’s Merchant Reserve and using glasses.

Jelani: Denizen’s Merchant Reserve is a blend of rums, all dark and Caribbean and delicious and made for classic punch-style cocktails. I tried it with this rum at Gage, among other rums, but this one really shined and was the obvious choice for this punch. This is the way that we serve it and Gage & Tollner and I hope you like it.

Chaos

Second Audience Member: While we’re talking about dilution, could you comment on the importance of the vessel that the cocktail is served in to preserve and evolve the experience for the end-user?

Garret: With flash blended drinks, it’s important that the glass is chilled. If you go to an old-school place, like the Mai-Kai in Fort Lauderdale, they keep most of their glassware in the freezer. Some of those glasses also have ice molds in them, which will keep that cocktail chilled for a longer period of time after it’s served. I think it’s a mistake to think that because a drink is going to be on crushed ice, it’ll be cold enough. You’d be surprised how fast ice melts in a room temperature glass.

Leanne: About what Jelani was saying on how every cocktail is different—every day is different as far as the environment goes. If you have an extremely humid day, if you have a cold day, if my tins won’t crack because there’s too much atmospheric pressure because it’s about to rain, all of that affects the drink. It’s really nerdy. But what Garret’s talking about, keeping your glassware chilled, all of that helps us counterbalance that.

Ben: How do you just adjust for atmospheric pressure?

Leanne: I ask my barback to crack my tins.

That’s one of the cool things about drinks and food and bars is that nothing will ever be consistent. We’re always changing. We’re always adjusting to what’s happening. And drinks do the same thing. Your ice might be really wet one day and you’re going to have to adjust how you shake your drink. I kind of like that adventure. I know it’s not ideal and it’s not perfect and it’s definitely not scientific, but it’s our reality behind the bar every day. It’ll be the same if you’re making drinks at home or you’re behind a cocktail bar, you can’t control anything and I kind of like it.

Jelani: Chaos!

Fourth Audience Member: I have a question about Garret’s pronouncement that we’re going to see salt in everything by 2027. If salt’s going to make that jump, do you ever see it going into the simple syrup instead of being its own thing?

Jelani: What?!?!

Leanne: People do that! That’s a thing.

Garret: There’s a couple of problems with salted syrup. One, you can’t adjust for conditions like atmospheric pressure—

Ben: We’ll get the Weather Channel as our sponsor next time.

Jelani: I can’t handle this!

Garret: Two, if you want to get super nerdy, salt and sugar look the same to a refractometer, which is what measures the sweetness of the syrup. It’s going to throw your readings off. Also, more importantly, some drinks require more of a particular syrup than others, right? And drinks need different amounts of salt. Something that has fresh cucumber juice, you may want to go a little bit more. A spicy mezcal drink, you want to go a little bit more. Something that doesn’t have a lot of acidity, you’d go less. When we make the Remember the Maine at Sunken Harbor Club, we only use three drops just to enhance the acidity of the Carpano Antica. I think, though, you probably will see that. Will I endorse it? No.

Jelani: Sir, I think you’re going to hell for even suggesting that we salt our simple syrup. And you guys…should not have been part of that.