With its rich ingredients and warming spices and spirits, it’s easy to see how eggnog has long been associated with the winter months. Yet even in the Caribbean with its balmy Decembers, eggnog remains both popular and strongly connected to the holiday season. National variations, like Ponche de Creme in Trinidad and Tobago and Coquito in Puerto Rico, share common heritage with eggnog while showcasing characteristics derived from the unique histories of their homelands.

Eggnog, as a spirituous drink, originated in colonial America, but did not survive Prohibition with those spirits intact. After repeal, boozy versions have returned with the craft cocktail revival. Recipes for eggnog often differ only on the ratios of the same seven or so ingredients: aged spirit, sugar, cream, nutmeg, cinnamon, and of course, eggs. But eggnog’s antecedents had more diversity.

An English predecessor to eggnog known as posset consisted of boiled milk curdled with sherry or ale. Posset likely influenced a more solid confection called syllabub and a related beverage, the flip—a beer, rum, and molasses combination heated to a creamy froth by a red-hot poker. Flips became common in North America when Caribbean rum became easily available and remained popular into the nineteenth century.

In this era, brewed beverages and the libations made from them were appreciated as much for their nutrition as their flavor. Cider, and a beverage made from it called switchel, offered calories, antioxidants, and electrolytes and was valued for refreshment during summer months. Stout and porter offered the mood-boosting benefits of beer, but were also brewed with nourishing ingredients like lactose and oatmeal. Appreciated during colder months, these thicker beers were enjoyed both by themselves and as components of flips.

Over time, perhaps in parallel with the growing American obsession with iced drinks, flips lost their fire, developing into cool drinks whose frothy texture came from egg white. Most flips no longer included cream, rum, or beer.

Guinness Punch

In the Caribbean, these omitted ingredients live on as a beverage popular locally but little known elsewhere, typically referred to as Guinness Punch or Stout Punch.

In the early 1800s, the Irish beer behemoth Guinness shipped a stronger version of their signature product called West Indies Porter to British colonies across the globe. In the Caribbean, it was popular with dock workers, who made a kind of flip with Guinness, cream, and locally-produced rum, calling it Guinness Punch.

Despite the name, modern recipes for Guinness Punch don’t always include a Guinness product; in Jamaica and Trinidad respectively the locally made Dragon Stout and Royal Extra Stout are also popular. The producers of Dragon Stout even market a stronger, sweeter version called Spitfire especially designed for use in such concoctions.

Today, there is a lack of consensus on the type of stout or rum to be used in a Guinness Punch, and views differ on adding ingredients like oatmeal or nutmeg. But almost all recipes agree on the need for Supligen, a vanilla-flavored milk beverage from Nestlé popular in the post-independence, English-speaking Caribbean.

In Trinidad, a version of Guinness Punch called Brown Cow made with Forres Park Puncheon Rum, Supligen, and stout is now typically regarded as a rural rum shop staple. In some areas of the country, it experiences a resurgence during the holidays as part of nostalgia for old-time traditions. Despite this, it comes nowhere close to rivaling Ponche Crema in terms of importance to a true Trinbagonian Christmas.

Ponche Crema

Ponche Crema emerged from a Latin tradition within the egg cocktail canon that developed independently of its Anglo-American cousin. Along the western Mediterranean, variations on a custard confection are often credited as the invention of a Catholic saint from the sixteenth century.

The story goes that Franciscan Friar Paschal Baylón used eggs, sugar, and wine to create a nutritional supplement that was easy for bedridden patients to consume. In time, variations on the words San Baylón would come to refer to several related desserts in the region. Zabaione is an Italian dessert typically made with Marsala wine. In France a similar dessert is referred to as Sabaillon, while in Spain it is known as Sabajón. In Tunisia, Sabayon is prepared without wine but with the addition of almonds and orange blossom water. The popular myth behind this name and family of desserts is complicated by the existence of a recipe for Zabaglione from a cookbook decades before Baylón was born.

In Spanish-speaking South America, Sabajón typically refers to a cream sauce, but in some parts of Colombia that name is used for a beverage of dwindling popularity that bears similarity to the more well-known Rompope from Central America or Ponche Crema from neighboring Venezuela. Of these beverages, Rompope’s early history might be the best documented; in her book Delicias de antaño (Delights of Yesteryear), Mexican gastronomist Teresa Castelló Yturbide traces Rompope to a Mexico City Convent founded in 1787. It likely emerged from the tradition of herbal tinctures and confections that the nuns sold in order to sustain the convent. Rompope and Ponche Crema resemble each other more than any other variations of eggnog, supporting the idea of a shared origin from the same Spanish tradition. Both can be aptly described as caramelized milk custard fortified with aguardiente de caña.

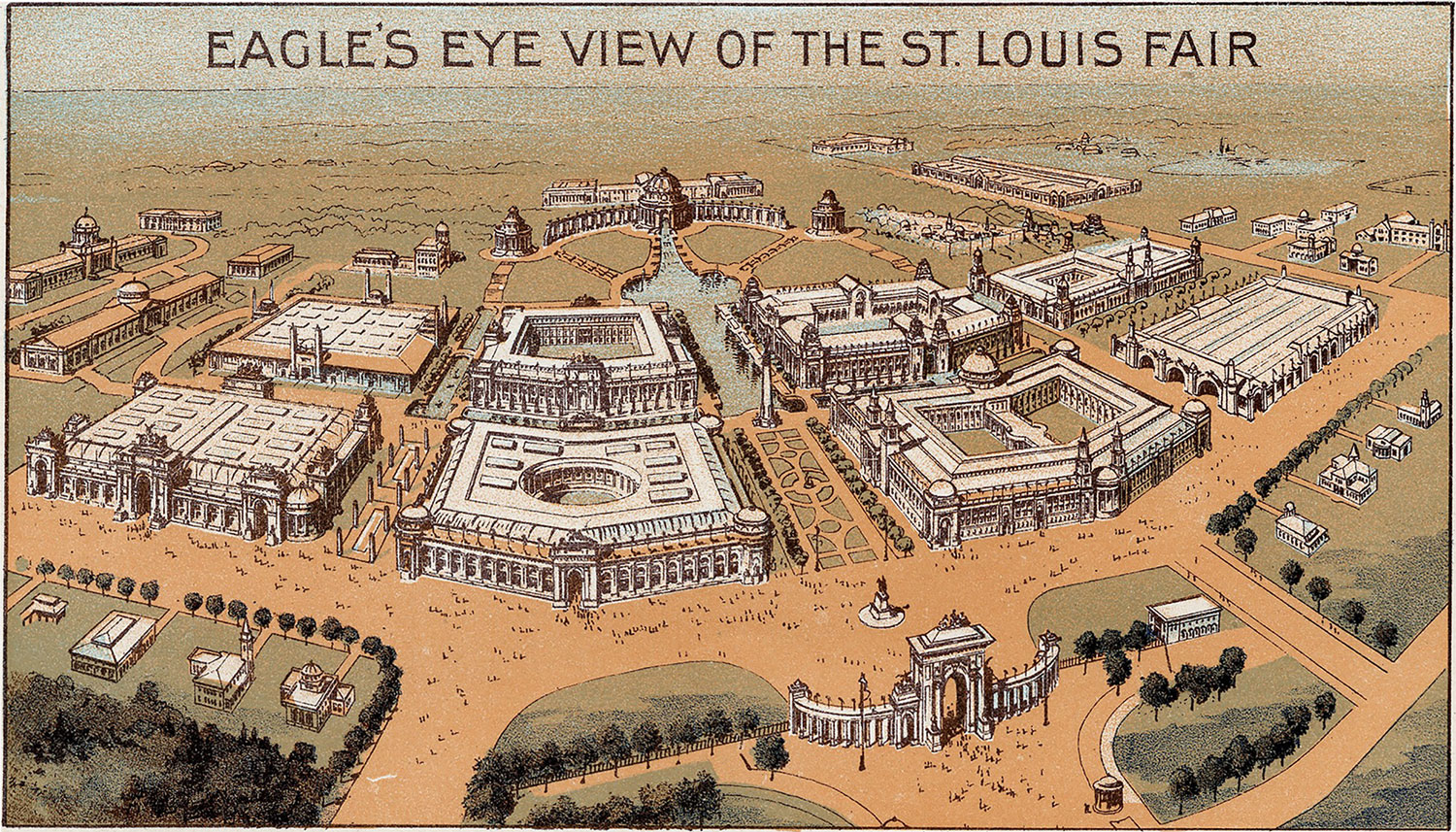

In the first decade of the twentieth century, chemist Eliodoro González Poleo created a shelf-stable version of Ponche Crema that he showcased at the 1904 Saint Louis World Fair as well as at exhibitions in Bordeaux and London in subsequent years. This was possibly the first commercial cream liqueur, and the brand is still popular in Venezuela today.

Through cultural exchanges, however, variations of Ponche Crema have found popularity in several islands in the south Caribbean.

Ponche de Creme

During the growth of Trinidad’s cocoa industry in the early 1800s, many migrant workers from the South American mainland moved to the island to capitalize on their experience with cocoa cultivation while also fleeing the strife of the Venezuelan war for independence.

These people of mixed Spanish and Indigenous heritage, referred to as the Cocoa Panyols, integrated themselves into the island’s Catholic Feast Day traditions, in the process introducing cultural elements that made Christmas appealing to non-Christians. In addition to Ponche Crema, this included a style of festive folk music called parang, and a savory cornmeal pie with Mesoamerican roots called pastelles.

The Trinbagonian tongue would shape a new name for this beverage: “Ponch-a-Crema,” a pronunciation made famous by a Lord Kitchener calypso. Similarly, the term “Ponche de Crème,” often now spelled without the accent, came from French Creole, once the language most widely spoken in Trinidad. Along with these naming changes, new methods of making the drink emerged.

Trinidadian mixologist Chad Lee Loy explains, “When you look at the recipes of the older merchant families, they do not look the same as the Latin American recipes.” According to Lee Loy, the more established French Creole and English families all had their own eggnog recipes and would often “entertain guests from the north during Christmas.” This influence from the North Atlantic brought inputs from fashionable cocktails of New York and New England of the time, particularly the Milk Punch described by pioneering mixologist Jerry Thomas in 1862 and the Egg Milk Punch that was essentially eggnog by another name.

Ponche de Creme in Trinidad became thinner than its cousin on the nearby continent, but it features a much more important defining characteristic: the inclusion of Angostura Aromatic Bitters. Dashes of bitters bridge the gap between dried spices and lime zest, itself another tropical addition in keeping with overall punch custom.

In Grenada and Barbados, a similar Ponche de Creme is popular, largely because of migration between those islands and Trinidad. In those countries, Ponche de Creme has largely displaced any older colonial traditions of eggnog or milk punch.

A common trend among these Christmas drinks in the Caribbean is an almost exclusive use of canned dairy products over fresh cream.

Agriculture in the English-speaking Caribbean was initially centered exclusively on export crops for the British market. Cattle were raised primarily for use as beasts of burden in the sugar cane industry, and both milk and beef were almost entirely imported as tinned products. The disruption of imports during the world wars inspired regional governments to update this archaic model of plantation production and focus on meeting local food security needs.

Global dairy giant Nestlé, which had previously only imported its products from Switzerland into Jamaica and Trinidad, began to invest in developing local infrastructure in those nations to support their growing demand for dairy. At the same time, researchers at the University of the West Indies worked on developing cattle breeds suitable to the Caribbean climate and able to be fed on locally grown crops.

Gary Garcia, a former professor of livestock science at the University of the West Indies who has written extensively on the use of sugarcane products to feed ruminants, recounts that there was “little real success” in developing a sustainable dairy industry in Trinidad. Despite this difficulty, many landowners continued to pursue mixed farming methods that included a dairy herd. Even with fresh milk being produced, University of the West Indies agronomist Tariq Ali says “for most farmers, it’s more feasible to sell milk in bulk to Nestlé instead of bottling and distributing it on their own.”

Accordingly, the majority of milk produced in Trinidad today is packaged by Nestlé and sold as one of their brands. Their products are deeply entrenched in local culinary culture.

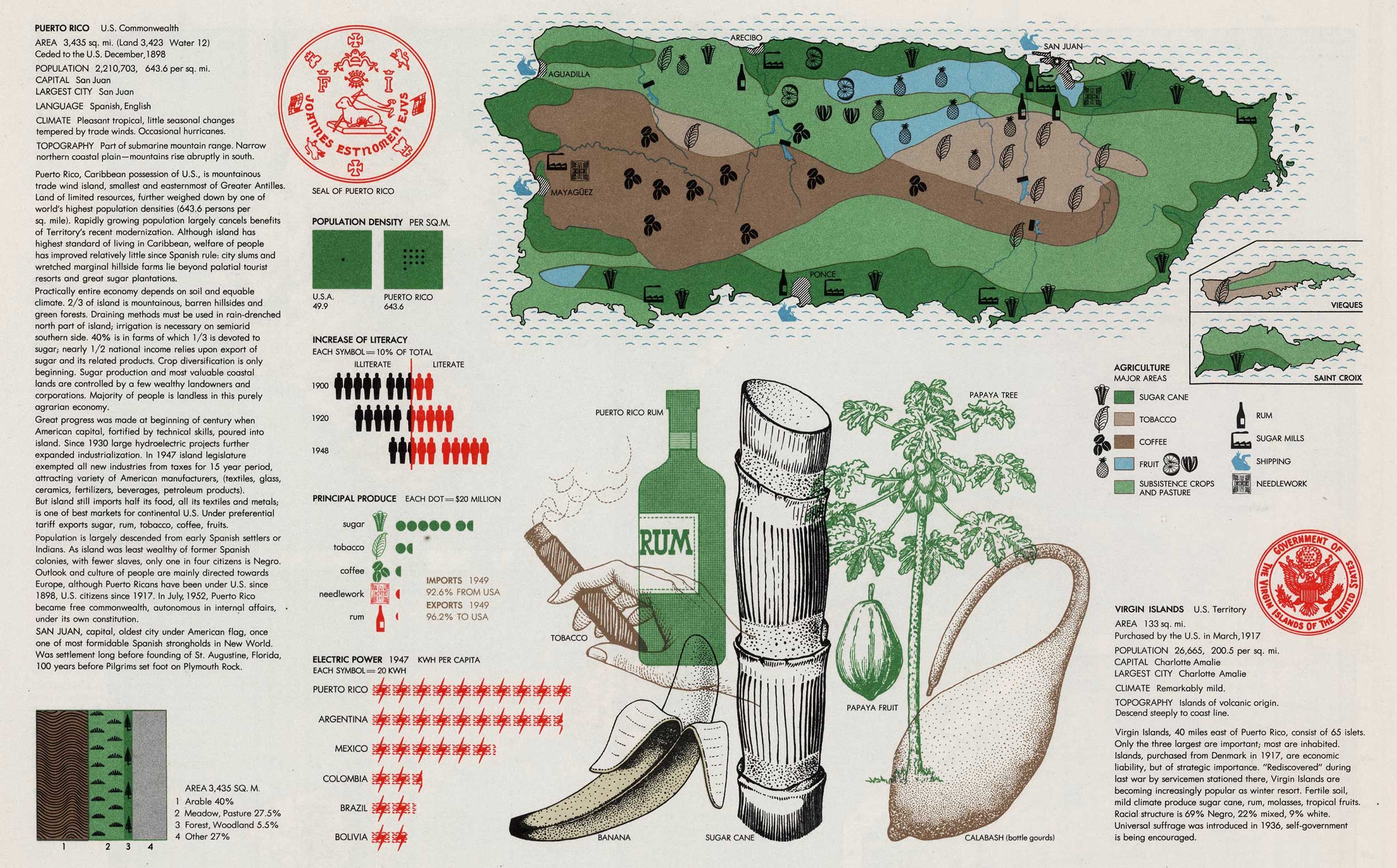

Puerto Rican Coquito would be similarly defined by the importance and importation of canned goods over the course of the island’s history.

Coquito

Often referred to as Puerto Rican eggnog, although most recipes do not contain eggs, Coquito has become the beverage that defines the Puerto Rican holidays. Other than rum, it typically includes cream of coconut, coconut milk, sweetened condensed milk, and a blend of several spices.

Puerto Rican writer and anthropologist Israel Meléndez Ayala told us that through American colonization “the Coquito came as an exchange of what they brought with what we had.” He describes two major developments over the course of the island’s history that led to the modern Coquito.

The first of these came before American occupation, when agriculture dominated the economy of the island. Cattle were introduced by Spanish sailors to Puerto Rico and Hispaniola so that they could enjoy the occasional roast meat when they returned to shore. Cows roamed coastal areas increasingly lined with coconut trees that were similarly introduced. While both cows and coconuts were important sources of nutrition, it is very unlikely that either were milked during the early history of European settlers on those islands.

Tariq Ali and Gary Garcia both pointed out some possibilities on how such a drink might have originated in the nineteenth century. The practice of rearing cattle under coconut palms, likely pioneered in ancient Sri Lanka, has proven beneficial to small farmers in tropical climates across the globe.

When trees are spaced far apart to achieve maximum coconut yield, the orchard becomes a shaded area where cattle can graze with some protection from direct sunlight. The manure from the cows then strengthens the soil, allowing the typically weak-rooted trees to grow taller and bear more coconuts.

In the Caribbean, a grass species brought to the region on slave ships has contributed further to this synergy. Cori grass or para grass is shade tolerant, sod forming, and relatively short so that farmers can easily find fallen coconuts. As feed for cattle, it out-competes unwanted shrubs but manages to coexist with beneficial legume species. Keeping cattle alongside coconuts allows farmers to save money on estate maintenance, while also offering improved food security.

This farming model was promoted in the early part of the last century and is still present in the Caribbean today. There is difficulty in determining the earliest examples of such farming in the region, since early census reports of agriculture were focused on plantation crops for export and ignored smaller subsistence farming. Additionally, landholders might have found nothing particularly interesting in their livestock grazing among coconut trees until researchers began recording their findings in recent times.

It’s easy to imagine farm workers in Puerto Rico simmering some milk from the coconuts they grew and the cows they raised before adding some pitorro (sugarcane moonshine) and panela (unrefined loaf sugar) from a nearby sugar mill. Such a tradition existing on small coconut plantations in the Caribbean might explain the predominance of cocktails similar to the Coquito, like Coco Punch in Guadeloupe or Haitian Kremas, where traditional recipes also call for fresh coconut milk.

The second factor that Ayala cites was the presence of the United States in Puerto Rico at the turn of the twentieth century.

In 1898, the United States invaded Puerto Rico as part of a larger campaign waged against Spain, in the process acquiring several Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The next year, two hurricanes leveled agriculture in Puerto Rico, creating a ready market for American canned goods like corned beef and condensed milk.

American policy would go on to play a key role in shaping the Puerto Rican diet. The Jones Act, designed to protect the American maritime industry by requiring goods shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on ships built, owned, and operated by U.S. citizens, would keep Puerto Rico ports dependent on American shipping companies. This resulted in a higher cost of living for the island and a heavier reliance on the canned goods introduced by Americans.

Operation Bootstrap, aimed to develop and modernize the Puerto Rican economy, led to a situation where agriculture, described by Ayala as the “cornerstone of Puerto Rico’s economy, employing nearly 45 percent of the work force” in the 1940s “started to be abandoned.” The sector currently employs less than three percent of workers on the island. From 1950 to 2007, the amount of land dedicated to agriculture decreased by three quarters.

But investment in manufacturing under Operation Bootstrap led to the invention of a sweetened, concentrated coconut product called cream of coconut, often known by the chief brand, Coco López. Invented by a former agricultural professor from the University of Puerto Rico, cream of coconut is closely associated with the Piña Colada, a mid-century creation now considered the national cocktail of Puerto Rico. Cream of coconut is also one of the required traditional ingredients in most Coquito recipes, so its advent meant that everything required for classic Coquito was available by the middle of the 1950s.In Eating Puerto Rico: A History of Food, Culture, and Identity, food historian Cruz Miguel Ortíz Cuadra writes that “the decades between 1950 and 2010 have been the scene of multiple, complex, and overlapping changes, including: the mass production and supply chain distribution of foodstuffs produced in Puerto Rico and on the mainland” and “higher personal and family income levels—especially between 1950 and 1980.” This was in contrast to past eras when changes to Puerto Rican culinary culture came about more slowly. These upheavals likely led to Coquito, and the canned goods used in making it, becoming strongly associated with Puerto Rican identity and past traditions. At this same time, increased North American influence and cultural hybridization led to the inclusion of eggs in some Coquito recipes.

Colonialism and Nostalgia

As Debbie Quiñones, who for many years hosted a Coquito competition in New York City, puts it, “the ingredients represent colonialism and imperialism as well as Caribbean culture.”

Reflecting on the global origins of Coquito’s ingredients, Quiñones says, “Here we are a colonized people, and we take these ingredients and we transform them into something that’s resilient.” In a sense, the reality that developing states on small islands rely heavily on imported non-perishable goods manifests in resilience. An example is in the winner of 2021 World Food Prize, Trinidad-born Dr. Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted, who researched the nutritional importance of small fish species and developed sustainable methods to get them on more plates. Her inspiration was the tinned fish that her grandmother credited as the “brain food” that brought the academic success of the first scholarship winner in the family. Nostalgia regarding canned goods and their place in the culinary culture of Trinidad combined with the personal resilience of a Trinidad-born researcher now contributes to improved food security globally.

In Caribbean cultures, canned goods also symbolize safety for both the region and the diaspora. For many who have left the Caribbean due to economic or ecological issues, they offer an affordable way to enjoy familiar dishes in an unfamiliar land. There is a sense of solace in being able to make Coquito or Ponche Crema anywhere in the world. In the Caribbean itself, as the Atlantic hurricane season typically concludes at the beginning of December, there is a sense of serenity in knowing that there are no storms on the horizon and that non-perishable supplies purchased earlier in the year as a precaution may instead be used for Christmas celebration.

The ingredients of these Christmas beverages also contribute to their sentimental value and sense of security. Yisell Muxo of Don Q Rum told us, “I think that adding cream gives a drink a sort of comforting feeling, as not only does it coat the palate differently, but in sweeter drinks the cream helps balance the sweetness.” Muxo sees these beverages as the comfort food of the cocktail world, and Coquito in particular as embodying what the holiday season means to many Puerto Ricans. She also notes the importance of passing on recipes and the pride in this tradition: “Each family has a different recipe (and some have several) and everyone makes it their own.”

It’s easy to dismiss these beverages as sweet, smooth, and shareable, but behind the silky texture, Ponche de Creme and Coquito highlight the complexity of Caribbean cultures, where products that represent the legacy of colonialism are also closely linked with endemic Caribbean traditions. The drinks are a product of converging and diverging customs across the islands, which offer insight into how colonialism produced the resilience that blossomed into nationalism. They show what Christmas, as well as community, means in the Caribbean.

Traditional Trinbagonian Ponche de Creme

Traditional recipe, adapted by Aneil Lutchman

2 cups rum

2 cans evaporated milk

2 cans condensed milk

6 eggs

1 tablespoon grated nutmeg

1 tablespoon ground cloves

1 tablespoon star anise

1 lime

Angostura Aromatic Bitters

Peel the entire lime, being careful to avoid pith. Combine eggs and peel in a bowl and beat with an electric mixer. Add evaporated milk and condensed milk and mix well. Add the spices, generous dashes of Angostura bitters, and rum, and mix well. Strain, bottle, and refrigerate.

Coquito

Recipe by Israel Meléndez Ayala, adapted by Aneil Lutchman

2 cups coconut cream (unsweetened)

1 cup white rum

1 cup aged rum

1 cup condensed milk

1 tablespoon ground cinnamon

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

In a bowl, combine all ingredients. Bottle and refrigerate overnight.

Trinitario Stout Punch

Traditional recipe, adapted by Aneil Lutchman

2 cups Ponche de Creme

2 cups chocolate stout

1 cup rum

Angostura Cocoa Bitters

In a bowl, combine all ingredients, adding bitters according to taste. Bottle and refrigerate overnight.