Sugar and spirits have enjoyed a cheerful partnership in our cups since the fifteenth century. Expensive and relatively rare, sugar was treated as a mood-lifting drug, making frequent appearances in boozy cure-alls at the bedsides of elite Elizabethans. By the eighteenth century, the sugar/spirits combo had moved from curative cup to punch bowl, finally settling into single servings sometime during the early 1800s.

In those bygone centuries, sugar was a bit different than the sweet stuff of today. Pure white sugar, the most expensive type available, was primarily used in the wealthiest kitchens for sugaring fruits rather than sweetening beverages. The cheapest sugar was dark and sold still sticky with molasses, and was typically used for curing meats and making savory culinary sauces. The next best sugar, pale golden yellow due to inclusions of molasses, was the one used for sweet syrups, homemade cordials, punches, and mixed drinks until the nineteenth century, when refined white sugar asserted dominance.

No matter what the quality, the sugar of that time was pressed into easy-to-ship one to ten pound loaves which had to be grated—or pounded—into useful granular form. In fact, many eighteenth century punch recipes called for using loaf sugar to abrade the peel from citrus, which gives an idea of exactly how hard those sugar loaves must have been.

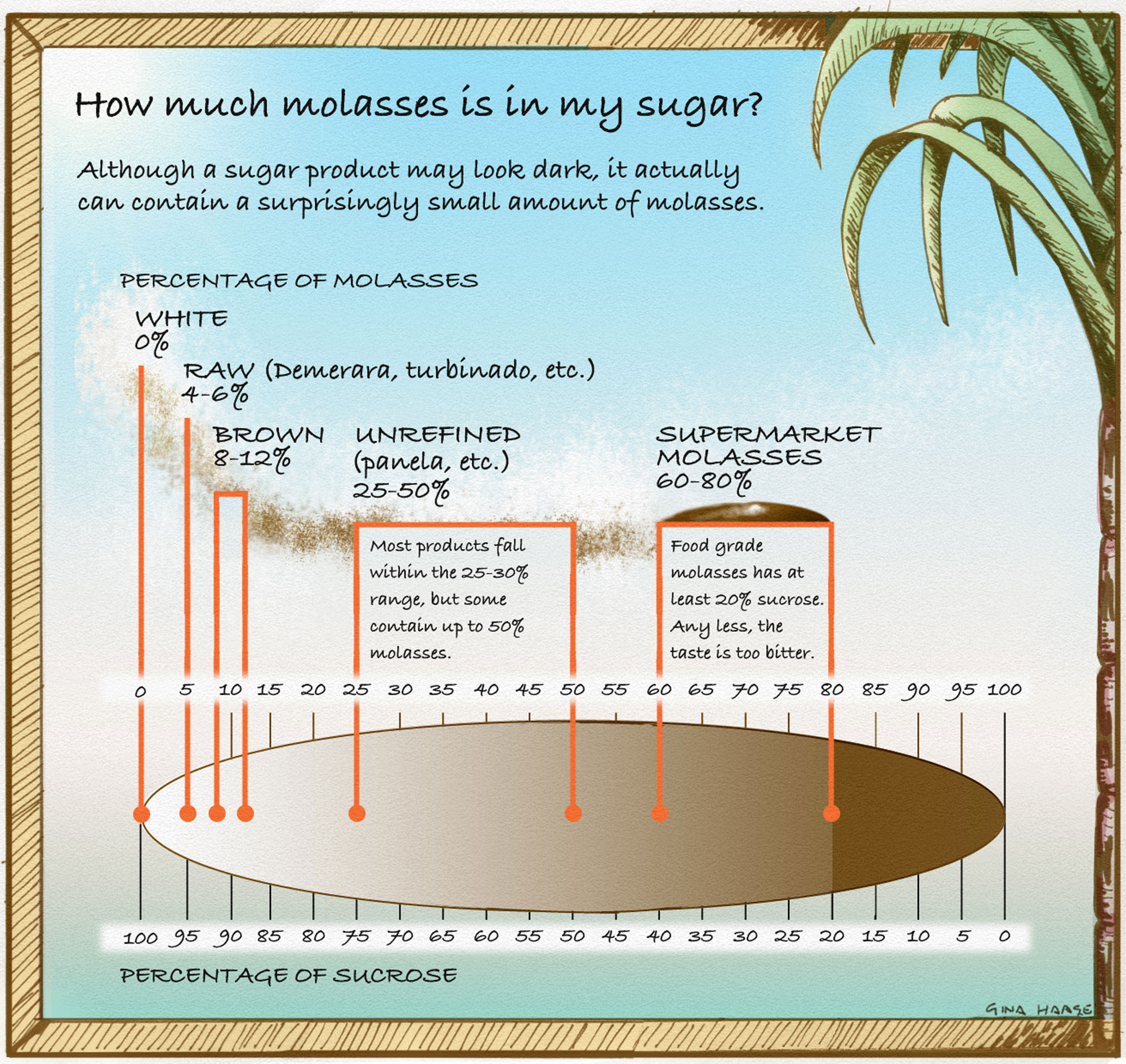

Nowadays, there are dozens of sugars to choose from. White, brown, raw, organic, or otherwise, the main ingredient in every product labeled “sugar” is sucrose—the organic chemical compound we call “sugar”—and the difference between the products lies in how much non-sucrose stuff is also in the mix.

Sugar and Its Integral Parts

White crystalline sugar, the sugar in nearly everyone’s bowl, is 99.8% pure sucrose. This white, odorless, sweet-tasting molecule is composed of two linked molecules, fructose and glucose. Sucrose is produced exclusively by green plants through photosynthesis, a process which uses sunlight as the energy source to convert water and carbon dioxide into sweet-tasting carbohydrates.

Many countries do not require labels to identify which plant the sucrose is refined from, but manufacturers typically mark “pure cane sugar” as such. Regardless, pure sucrose from one plant source is indistinguishable from that of another.

Ever since India’s invention of chemically-refined cane sugar over 2,500 years ago, it’s been the sugar producer’s goal to separate as much sucrose from the plant as possible. Sucrose is abundant in sugar beets, palms (sago, coconut, date, etc.), corn and other types of grasses, and most importantly, sugarcane, the source for over half the world’s sugar and the base of all rum production.

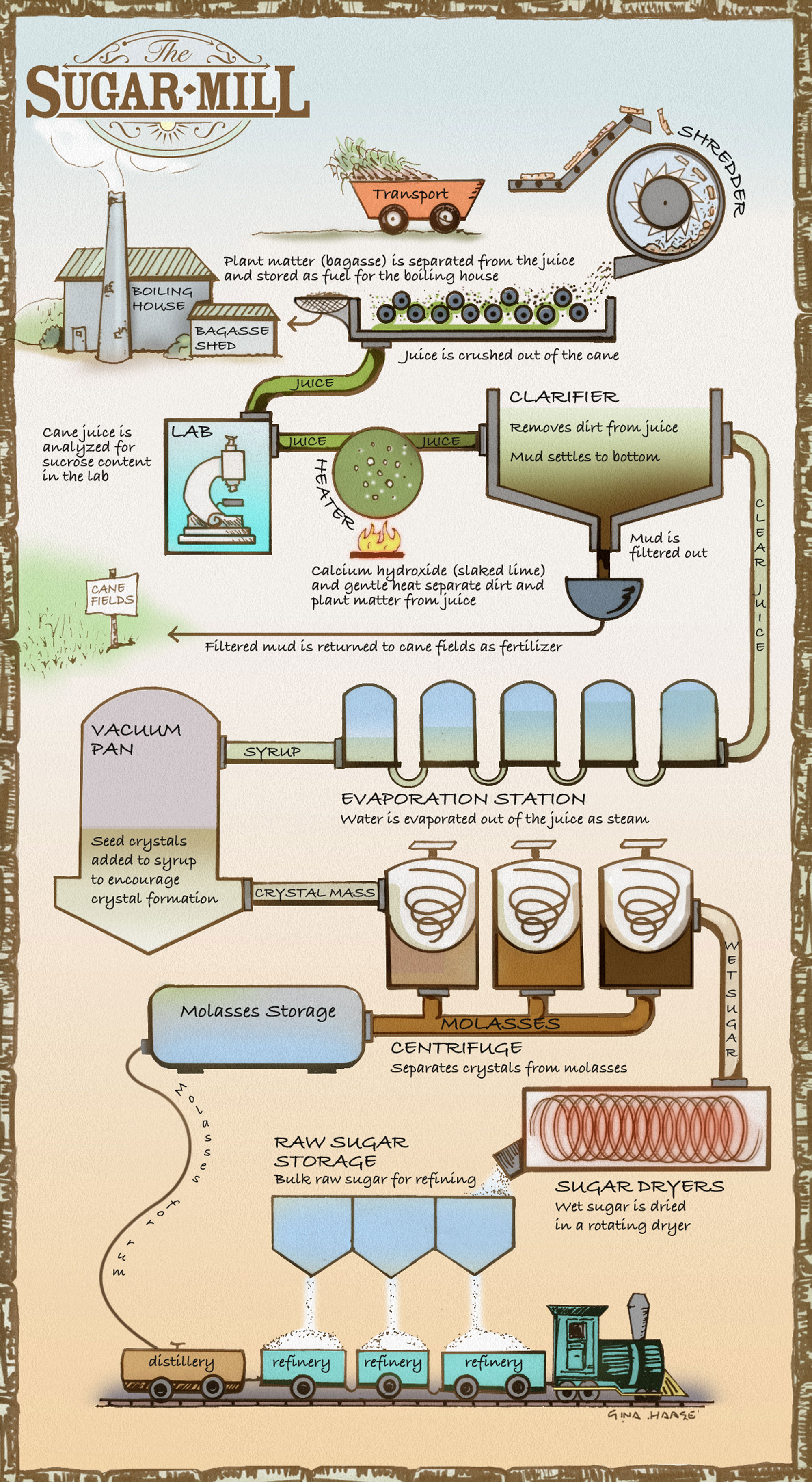

Freshly pressed sugarcane juice is a brownish-green, opaque liquid which contains 10 to 14% sucrose; the rest is plant matter, other sugars, water, and minerals. At the sugar mill, the thin juice is clarified and filtered to remove the solid bits. Next, the filtered juice is concentrated in a vacuum; as air is removed and the pressure is lowered, the boiling point of the juice drops. This crucial step allows the juice to boil at room temperature during the evaporation process, thereby preventing unwanted caramelization and excess sucrose loss. As the thick, brown, syrupy concentrate gently evaporates within the vacuum pan, tiny “seed” grains of pure sucrose are introduced to encourage crystal formation. Then the entire crystal mass is transferred to a centrifuge, spun to remove lingering liquid from the golden-colored sugar crystals, and dried.

At this point, the milled sugar crystals are typically not considered food grade. Batches of sugar crystals destined for rum production are sent off to the distillery, while those ultimately meant for the table are transported to the sugar refinery for further processing.

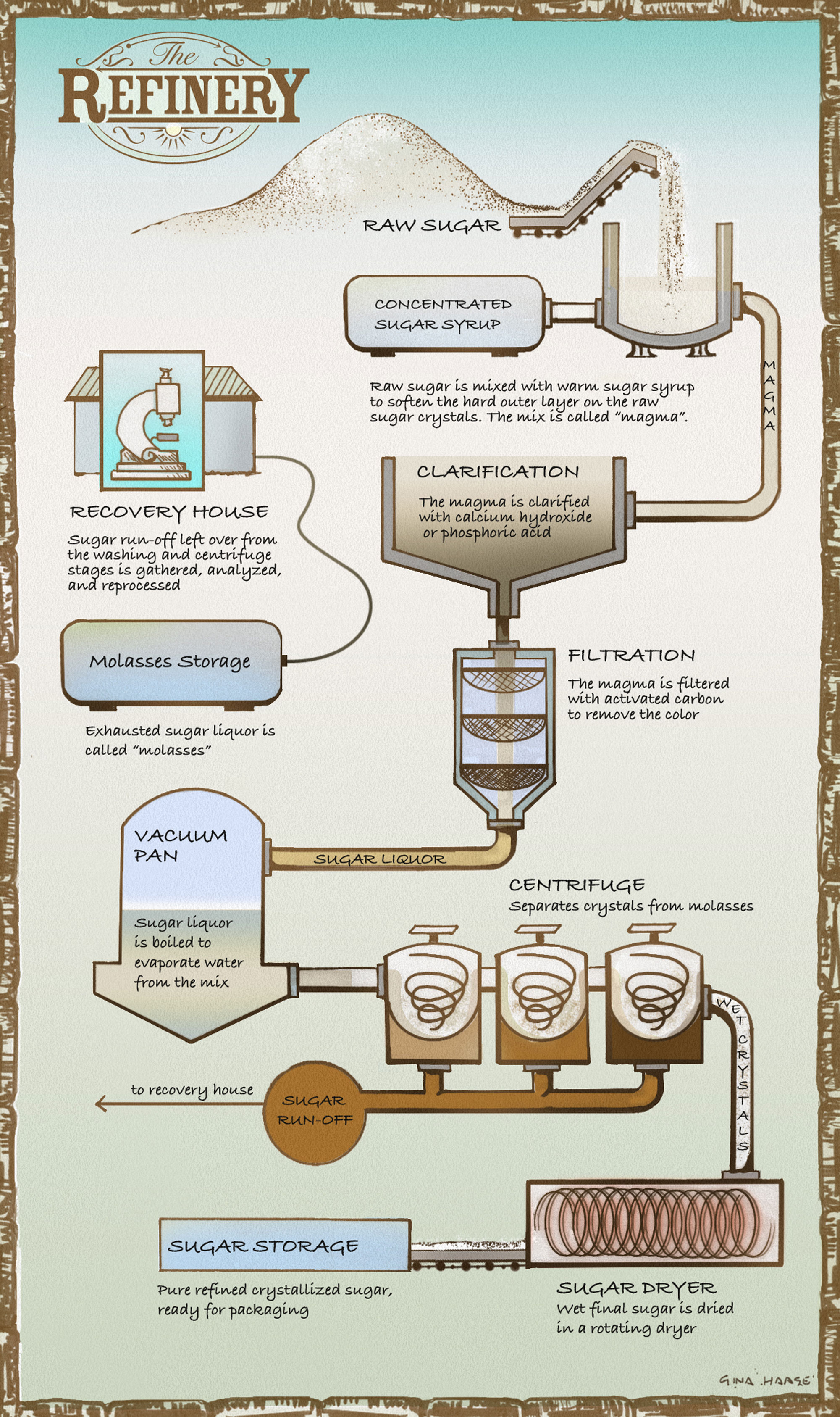

The refinery is responsible for all the products we think of as sugar. When the milled crystals arrive at the refinery, they are mixed with a hot sugar syrup to soften the brown outer coating, then the mixture is put through another centrifuge to remove some of that hard matter. The crystals are then remelted, undergo further clarification steps, and finally, are crystallized, spun through one last centrifuge, and dried.

The dark, sugar-rich liquid spun off from the crystallized sucrose during the centrifuge process is what we know as molasses. Also called treacle, molasses (from the Latin melaceres, “honey-like”) is a desirable byproduct used as a sweetener, food additive, colorant, and more. Grade A (the lightest molasses) is produced by the first spin. Later spins produce darker molasses labeled as Grade B, C, etc. When no further sucrose can be crystallized out of the molasses, the syrup left behind is called “blackstrap.” This represents the refinery’s loss and the distillery’s gain: blackstrap still contains considerable amounts of sucrose and all of the plant’s essence, making it the perfect raw material for rum production.

Molasses grades contain anywhere from 22 to 45% sucrose, about 20% water, and a varying combination of several dozen organic and inorganic chemical compounds inherent to the cane syrup. These compounds give molasses a pleasingly distinctive taste ranging from mellow caramel to harsh licorice.

Because the chemical composition can vary from batch to batch, molasses is tested for quality by burning off water and organic compounds (carbon-based molecules) to determine ash content. Although the word “ash” inspires visions of grey dust at the bottom of a fireplace, ash refers to all the inorganic compounds found in the molasses. Ash is composed largely of the essential minerals iron, phosphorus, and calcium along with potassium, magnesium, and sodium salts, but can sometimes include toxic materials like mercury, cadmium, arsenic, and lead, which is why testing is so important. Toxins aside, too much ash can make the molasses too acidic, so a low ash content is preferable.

Molasses also contains a naturally-occurring syrup produced during the evaporation step. Called invert (or inverted) sugar, this sticky, hygroscopic (water-attracting) solution of equal parts glucose and fructose is the result of acid hydrolysis: Heat, combined with cane juice’s natural acidity, breaks the link between sucrose’s constituent parts. The name “invert” refers to the process of inverting the rotation of polarized light. In other words, when a beam of single-colored light shines through a sample of invert sugar, the emerging light doesn’t travel in a straight line; it rotates about twenty degrees counter-clockwise. Does this affect flavor? Not at all. Invert sugar adds viscosity to molasses, and its water-attracting qualities help keep microbial contamination at bay.

Incidentally, invert sugar is also produced as a commercial product at the refinery. Variously called liquid sugar, liquid sucrose, or liquid invert, this mixture of approximately equal parts of glucose and fructose is made by inverting sucrose via enzymatic hydrolysis, a natural process which uses the enzyme invertase to catalyze the hydrolysis of sucrose into a very stable syrup with low water activity. An imprecise version of invert sugar can also be made at home through acid hydrolysis by heating together ordinary white sugar, water, and a pinch of citric acid (makers of confections and pastries do this all the time), but this is a far less shelf-stable mixture which is prone to browning over time.

White Sugar, Also Known as Pure Sucrose

Refined white sugar is pure sucrose (“refined” being another way to say “purified”). Left to its own devices, pure sucrose will form monolithic crystal structures, so sugar manufacturers manipulate the size of the grains during the crystallization process to create a wide range of granularity.

Table sugar, granulated sugar, castor (or “caster”) sugar, fruit sugar, baker’s special sugar, superfine sugar, ultrafine sugar, and bar sugar are all pure sucrose: the only difference is the grain size.

Extra-coarse sanding sugar is a large-grained refined white sugar. The grains are polished to reflect light and often have a harmless wax coating applied for extra shine.

Lump sugar and rock sugar are very large, irregularly sized crystals of refined white sugar. These are crystallized from a supersaturated solution of sugar and water.

Pearl sugar, also called hail sugar and nib sugar, is a non-crystallized refined white sugar made by crushing large blocks of sugar (picture those eighteenth-century loaves), then sifting to obtain fragments of a given diameter. Pearl sugar is hard, opaque, and bright white.

Confectioners’ sugar (also called powdered sugar or icing sugar) is finely pulverized, refined white sugar with 3 to 5% cornstarch or tapioca starch added by volume to prevent caking.

Sugars that Include Molasses

Molasses is the essence of the sugarcane plant, lending its warm note to brown sugars. A versatile byproduct, it also adds color, flavor, and texture to many types of food, and provides rum with its characteristic aroma and taste.

Raw Sugar

Raw sugar is a misnomer—sugar is not a food that exists in a raw or cooked state—but it is a generally accepted term used to describe any minimally processed crystalline sugar which contains trace amounts of natural colorants and molasses. Also known as evaporated cane crystals, washed sugar, raw cane sugar, and natural cane sugar, raw sugar tastes as sweet as pure sucrose, but the 4 to 6% molasses content gives it a pleasant sugarcane aroma and light caramel flavor.

Turbinado and Demerara sugar are two common names (sometimes used together, and often used interchangeably) for raw sugar. Turbinado is a Portuguese loanword, named for the turbines that spin the sugar. Sugar In The Raw is a familiar American brand of processed turbinado sugar. “Demerara” once referred to sugar produced in the historical colony of Demerara in Guyana, but it has never been a protected designated origin. In 1913, the British legal case of Anderson vs. Britcher found that Demerara sugar “had become a conventional term, and that it need not be grown in Demerara, just as a Brussels carpet need not necessarily be made in Brussels.”

“Evaporated cane juice” and “dried cane syrup” are deceptive marketing terms for sugars that include molasses. These products are produced in exactly the same way as other sugars, but the word “sugar” has been omitted to appeal to the health food market. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) discourages producers from using these terms on their sugar products, but it does not regulate them.

Brown Sugar

Brown sugar is the name given to a very specific combination of pure sucrose crystals, molasses, and invert sugar.

The Codex Alimentarius—the internationally recognized collection of food standards, codes, and guidelines put together by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations—mandates that all commercially produced brown sugar contain at least 88% sucrose, in addition to molasses (which provides flavor) and invert sugar (which adds softness).

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has different regulations. It requires that any product labeled as brown sugar must be made from sucrose obtained from sugarcane or sugar beets, and the finished sugar must have a soft texture, uniform brown color, and a sweet molasses odor and flavor. Ash content cannot be more than 2.25% (3.25% for dark brown sugar products) and maximum moisture cannot exceed 4.5%. (The FDA does not regulate brown sugar per se, it only regulates how it’s prepared, packaged, and labeled.)

Ash and moisture content are the biggest compliance concerns, so to meet the USDA’s exacting standards, manufacturers often produce conventional brown sugar by adding precise amounts of sugarcane molasses to pure sucrose crystals. Other manufacturers seeking to label their brown sugar as “natural” (an unregulated term) take a slightly different approach, refining the sugar in the usual way until the sucrose-to-molasses ratio reaches the target numbers. Those using sugar beets as the base for their brown sugar product cannot utilize this “natural” approach, as sugar beet molasses tastes distinctly of beet!

It’s good to note that in the United States, there’s often very little difference in the molasses or sucrose content of conventional light and dark brown sugar. Both sugars can be manufactured from the same batch of sucrose mixed with molasses. The differing hues are courtesy of caramel coloring, which has minimal impact on flavor.

Unrefined Sugar

Unrefined sugar (also known as whole cane sugar, and marketed under a plethora of regional names) is the least processed style of crystalline sugar. It is made from crudely clarified evaporated sugarcane juice, and contains anywhere from 50 to 75% sucrose, with the rest being invert sugar, plant proteins, ash, and molasses.

This type of sugar is often produced by an “open pan” process—the juices are simply boiled outdoors in open containers—or indoors by mechanically stirring the boiling juice until a sludgy mass of crystals forms. The crystals are then transferred to molds and left to harden. The solid block, loaf, and cone shapes of the molds reflect colonial transport practicality.

Other than the salient characteristics (sucrose content, taste, odor, color), unrefined sugars are generally unregulated in the U.S. However, they must comply with all applicable federal and state mandatory requirements and regulations relating to preparation, packaging, labeling, storage, distribution, and sale in the commercial marketplace. As a rule, unrefined sugars taste about half as sweet as pure sucrose and are very molasses-forward. Depending on the ash content, they have either a mineral or vegetal aftertaste.

Muscovado sugar (sometimes referred to in older texts as Barbados sugar) was an early seventeenth century form of inexpensive, unrefined sugar. The name muscovado comes from the Portuguese phrase açúcar mascavado (“sugar of the lowest quality”). Today, there is no international standard or legal definition of muscovado production, so modern products labeled as muscovado can vary from dark to light, moist to nearly dry. Sucanat (the name is a contraction of the French phrase “sucre de canne naturel”) is a brand of unrefined sugar marketed as a substitute for muscovado.

Mexico’s piloncillo (“little cone”), Central and Latin America’s panela (“little loaf”), Brazil’s rapadura (Portuguese for panela), and South and East Asia’s khand, khandsari, and jaggery are all regional names for unrefined sugar. The word “jaggery” comes from the late sixteenth century Portuguese jágara, borrowed from the Sanskrit word sárkarā (“gritty substance, sugar”). The names khand and khandsari are a nod to khanda, India’s first commercial non-refined sugar form (which dates back to 500 B.C.).