Something has been happening in the dark.

While American craft beer and whiskey gobbled up most of the headlines over the last several years, rum—the spirit that first captured the nation’s heart centuries ago—has quietly reingratiated itself to a growing number of distillers. For the first time since the eighteenth century, you can once again find hundreds of distilleries producing rum across the United States.

This isn’t necessarily breaking news for hardcore rummies. The idea of an American rum revival has been percolating for a few years across the rum festival circuit, along with the occasional media mention. But even the category’s most ardent followers will offer a bit of surprise when that vague notion of a revival is translated into actual numbers. When I first started compiling an index of American rum producers in February of 2019, the initial tally came in at 220. It has already swelled well beyond 250, with word of missing distilleries that need to be added reaching me on a weekly basis.

Somehow, in the span of around a decade, the U.S. has found itself with the second highest number of rum-producing distilleries in the world, trailing only Haiti and its estimated 500-600 small producers of clairin, the island’s own unique take on rum.

It’s only natural to wonder what’s driving so many American distillers to suddenly produce a spirit that’s almost universally associated with the Caribbean and Latin America. It’s also natural to wonder how much of it is actually good.

The Dual Forces Behind America’s Craft Rum Boom

Pose those questions to the people making it and you’ll learn there are generally two types of American rum distillers—those who make it out of love for the spirit, and those who make it so they can have something to sell beyond whiskey and gin.

“There are some distilleries that are like, ‘I’m making rum, I love rum, I’m in the service of rum, I’m connected to rum, I think rum is great,’” says Maggie Campbell, who’s spent the last eight years making rum as president and head distiller of Privateer Rum in Ipswich, Massachusetts. “And there are some distilleries that are, ‘We’re going to extend our line, we’ve heard that rum is popular, I guess we’re making rum now.’”

The producers who fall in the former category like Campbell can nerd out with you on rum for hours. Throw out your favorite Caribbean rum and they’re liable to tell you about the most recent conversation they had with the distiller or master blender who brought it to life. They can give you an impromptu history lesson about their distilleries’ ties to the United States’ once thriving rum industry.

They can also tell you that, while they’re thrilled to see so many more American producers opening their doors and bringing more awareness to the category, the influx isn’t without its downsides.

“Now that rum is getting a little more popular a lot of whiskey people are looking at it as just a way to make some fast money, and they really don’t care about rum,” says Jonny VerPlanck, who’s been making rum in some form or fashion for over two decades. Before shifting gears to focus on consulting, VerPlanck helped Three Roll Estate in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, get production up and running as one of the only single estate rum distilleries in the country, producing rums from both fresh-pressed cane juice and molasses. “It’s good to see people come over to the rum category, but I think a lot of distilleries are looking at it in the way I look at vodka. I did a vodka at a rum distillery so we could sell vodka drinks strictly for revenue.”

VerPlanck wasn’t the only distiller who made this comparison. Andrew Lohfeld, co-founder and head distiller at Roulaison Distilling in New Orleans, wasn’t thrilled when he noticed it popping up on merchandise at industry event Tales of the Cocktail. “There was always this running joke printed on T-shirts that said, ‘Vodka pays the bills,’ and it broke my heart when I saw a T-shirt that said, ‘Rum pays the bills,’” he says. “I don’t know what that means, but I hope that’s in a good way and they’re not equating rum with vodka.”

It’s not that rum paying the bills is an objectionable concept to the distillers and founders who have spent years placing sizeable personal bets on the category. When I asked Karen Hoskin, who founded Montanya Distilling in Colorado eleven years ago, why so many producers are flocking to the category, she was quick to note that increasing market demand is a welcome development.

“I’d like to think that it’s because people recognize that it’s becoming a serious market force,” she says. “But the flip side, or maybe the underbelly, of that is it also means they’re not coming into it for the right reasons, which is that they are rum obsessed.”

In Hoskin’s view, obsession is simply table stakes for having any shot of producing rum that’s actually good. To the uninitiated distiller, rum can seem easier to make than the most in-demand types of whiskey since it doesn’t require aging or mash equipment. It’s only after their first batch that newbies often see the light.

“If I had $100,000 for every whiskey distiller who tried to make a rum on the way to their whiskey and were like, ‘What the fuck? I had no idea how hard this was….’” Hoskin says, leaving the hypothetical and all its implied millions to hang in the air before continuing. “I’ve been really working for the last decade to help people understand that making really good rum is not simple. It’s not a compromise. You’re not getting any benefits in the distilling process. In fact, sugarcane is probably one of the hardest things to ferment. Molasses is probably the hardest thing to ferment.”

For Better or Worse, We’re in This Thing Together

There’s a sense of responsibility among more seasoned American rum distillers to be stewards of the category rather than gatekeepers. It’s not their place to police newcomers, but many are more than willing to offer whatever knowledge they’ve accumulated to those who ask for it. They know the best way to convince more people to take the category seriously is to have more distillers making great American rum. While that might sound like helping the competition, Campbell from Privateer doesn’t see it that way.

“If someone has a North American rum and they hate it, they’re going to be so much less likely to try mine. And we’re not really competing with each other. If I sold every bottle of rum I make in a year, I would barely sell to the tiniest percentage of the population of Massachusetts,” she says. Giving other producers an inside look at Privateer’s process is Campbell’s way of paying forward knowledge so many in the global rum community have been willing to share with her over the years. “There is not a lot of cultural familiarity with rum in America. I sometimes see bad advice get out there and get spread really fast…the better it is for everyone, the better it is for me.”

Sam Pierce and Dave McConnell are among the latest examples of new American rum producers who spent time picking Campbell’s brain before opening their distillery. The two are co-founders of Three of Strong Spirits in Portland, Maine, which opened in June. As the name implies, they exclusively produce rum and plan to keep it the focus.

“Rum is not a gateway to other things. Rum is our core,” Pierce says. “We had people who advised us, ‘Oh, well, you have to go with a full portfolio of spirits right off the bat.’ Our short answer was we want to be very successful in a targeted area rather than have that just be a bridge to something else.”

For Pierce and McConnell, being successful in rum starts with an oft-repeated phrase—making it “the right way.” But what exactly does that mean? Besides hiring a head distiller who brought twenty years of experience to the table in Graham Hamblett (formerly the head distiller at Dogfish Head Distilling), it means being transparent.

“For us that means first and foremost being transparent about what we do, about our process,” McConnell says. “If we were going to add something to our rum—we’re not planning to color it or dose it with sugar—but if we were, we would say that.”

Ask the co-founders about the rum they’re currently making and that commitment to transparency seems to hold up. They’ll tell you it’s produced in a copper pot still from a fermentation of molasses and cane sugar (to accommodate for the lower levels of fermentable sugar in many forms of modern molasses). They’ll tell you the fermentation uses a wine yeast and takes place at a low temperature for over a week. They’ll also tell you the twelve-year-old rum they’re selling is sourced from a Colombian distillery, which is clearly indicated on the label.

The Colombian rum gives Pierce and McConnell a way to show customers what a premium aged rum can taste like alongside the unaged expression they currently have available—a concept that exposes an often overlooked detail of American rum’s influence on the category as a whole. While rum enthusiasts can taste an American rum and see it as a representation of only a small subset of the spirit, most visitors at American distilleries aren’t necessarily rum enthusiasts. An American rum is often the first one they’ve tasted since the Captain and Coke-fueled weekends of their youth. Whichever American rum they happen to sample is likely to influence their perception of the entire rum category, for better or for worse.

Finding the Category’s Gems

If you are a rum enthusiast, however, the question remains—how do you identify the American distilleries that truly care about making great rum versus those who see it as an easy line extension or placeholder for whiskey? Complicating the question is the fact that exceptions to the dichotomy exist. A distiller’s starting point with rum doesn’t always reveal much about the quality of their juice.

“To be honest, I made rum because nobody locally was doing it. My plan was actually to make rum and then eventually get into whiskey,” says Tim Russell, who founded Maggie’s Farm Rum in Pittsburgh in 2013 (he’s also the head distiller). “But the funny thing is once I got into rum…I kind of fell in love with it. We’ve never made anything else.”

That might be why Russell is hesitant to automatically write off rums that come from whiskey distilleries. “At this point, six years in, I know not to judge immediately. So I’ll wait to try anything first,” he says. Hoskin from Montanya Distilling also acknowledges that good rum can come from distilleries that don’t make it their number one focus. “The exception is like Leopold Brothers or St. George,” she says. “Companies who are using this incredibly high level of production expertise and incredibly high level of distiller knowledge in their Harry Potter lab.”

Jaime Windon, who co-founded Lyon Distilling as a rum-focused distillery in Saint Michaels, Maryland, recently swore off the distillery’s lauded experiments with rye whiskey in favor of recommitting herself completely to rum. “There is something that doesn’t sync up for me when someone walks in my distillery, tells me how much they like whiskey, I find them a rum they love, but then tell them to come back in a few months to try our whiskey,” she says. “Of course I like whiskey. I enjoy all spirits. But I love rum. How can I believe that all you need is rum and spend my time making anything else?”

The best tools for sussing out which distillers take their rum seriously are simple questions. VerPlanck rattles off a list he thinks would give any rum drinker an idea of a distillery’s level of commitment to the spirit.

“What style of rum are they going for? What are their raw ingredients? What kind of rum do they like to drink? Do they even drink rum? Do they know any rum besides Bacardi?” he says with a laugh.

These questions will often not only reveal a distiller’s knowledge of rum, but also the lengths that distiller has gone to produce it. One of the primary reasons Lohfeld and his co-founder at Roulaison Distilling relocated from New York to New Orleans, for example, was to have easier access to the type of high-grade Louisiana molasses they desired for their rum (a local mill puts aside a small quantity of less-processed molasses for them).

If anything, using domestically-produced sugarcane is a new feature of American rum rather than a revived practice of its past. The colonial rum era ran almost exclusively on imported Caribbean molasses, which was as cheap as it was plentiful. Of course, you’ll still find many American producers carrying along the tradition of using imported molasses. Campbell and the team at Privateer announced in June that they’d finally found their ideal sugar source after years of searching—a Guatemalan mill that provides them with a single origin molasses that’s “amazingly environmentally, socially, worker positive,” according to Campbell. In the modern era, however, the American producers who import molasses have much more in common with Caribbean rum distilleries, many of which now import their molasses as well.

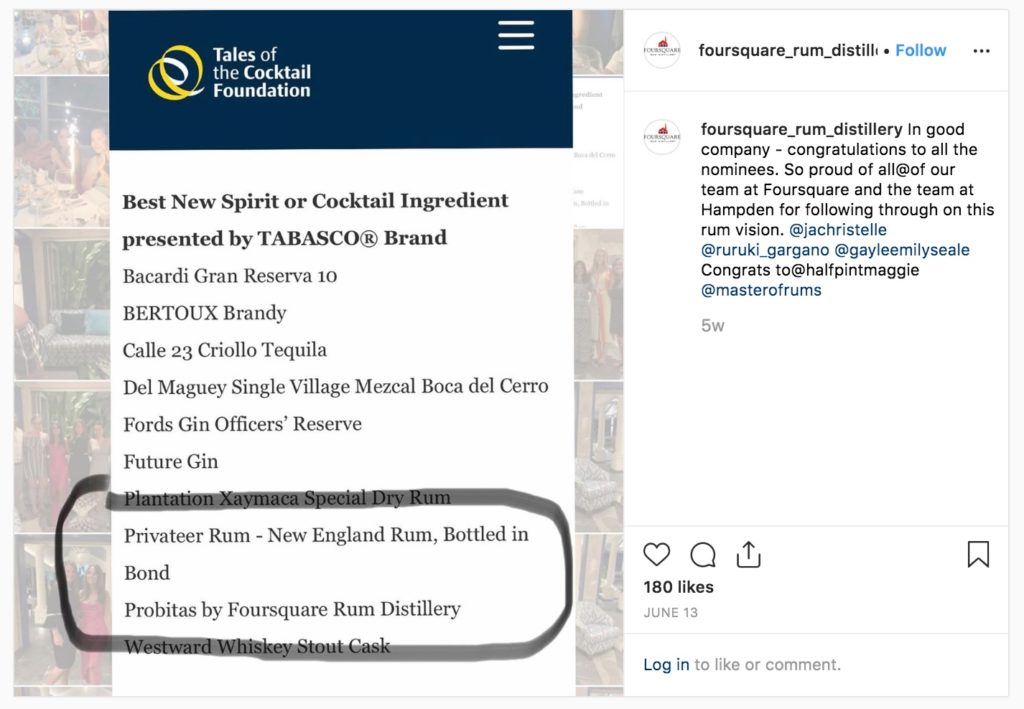

But quizzing American rum producers on their commitment to the spirit isn’t the only way to root out the ones most likely to be producing the good stuff. You can also look for signals of quality from the larger spirits community. For two years running, Tales of the Cocktail’s Spirited Awards has listed Privateer as a top ten nominee for the Best New Spirit or Cocktail Ingredient award. This year, the distillery’s Bottled-in-Bond New England rum shared the spotlight alongside Probitas rum (a collaboration between Foursquare Rum Distillery and Hampden Estate), Plantation’s Xaymaca expression, and Bacardí’s Gran Reserva 10. The best validation, however, may have came from a response Foursquare posted on Instagram following the nominations.

“Our nomination, because it was in alphabetical order, was right under Foursquare’s. When Foursquare put out their post, they circled both our names. It was really sweet. I was crying really hard,” Campbell says. Foursquare paired the photo with a caption that begins simply, “In good company.”

Awards aren’t the only signal a distillery may be onto something. Cash is another. Montanya Distilling announced in July that Constellation Brands made a minority investment in the distillery through its Focus on Female Founders program. Some of that investment will undoubtedly go into expanding distribution and production. Already available in 40 states and seven countries, Montanya is positioned to be one of the biggest influences on the market’s perception of the American rum category.

Still, with so many new American rum producers sprouting up every month, even the distillers who have been in the community for years admit it’s difficult to estimate the number of truly good American rums currently available. VerPlanck and Russell put the ballpark figure around twenty to thirty, but admit that’s based only on the fraction they’ve been able to taste. It’s possible that plenty of gems are still waiting to be discovered.

The best bet for consumers? Visit a distillery and ask as many questions as possible.

“Mostly I’m just glad that we’ve got more [distilleries] opening up, whether they’re in our own backyard or not,” Lohfeld from Roulaison Distilling says. “The more attention that the category is getting, good or bad, it’s at least posing those questions that are ultimately going to be good for the companies that are doing it right.”